These are my reflections on COP30, the first climate COP that I have attended. I would like to thank the Toha Network for supporting my travel, Brazil's Ministry of Finance for the invitation to pre-COP events in São Paulo, the New Zealand Government for the COP30 overflow badge, and the people of Belém for hosting the event with such an extraordinary spirit of hospitality and solidarity. All monetary amounts below are in USD.

The overwhelming sensation of climate COPs is one of excess.

Much more than a platform for international negotiations, the Conference of the Parties (COP) has become a multi-layered event that combines a trade fair, business summits, academic conferencing, cultural festivals, protest marches, and elite parties – all spread across two official zones and many other venues throughout the host city.

With so much going on, you cannot avoid a sense of mislocation, an unshakeable anxiety that you aren’t at the panel or ‘fireside chat’ that you most need to be at, that you aren’t hearing the right gossip or meeting the right person, that you’re somehow out of the loop no matter how thin you spread yourself. But this is the experience of being a single node in a complex human network – and it is the network which we entrust, rightly or wrongly, to deliver transformative change.

This year, COP30 was hosted in Belém, a riverside city in northern Brazil at the edge of the Amazon rainforest. This carried symbolic significance, but also logistical challenges, not least the dense equatorial heat. The air conditioning never really kicked in at the Blue Zone, the main conference hall, where up to 56,000 delegates moistly intermingled in the mind-melting temperatures.

In one sweltering session, Kim Stanley Robinson, author of The Ministry of the Future, reflected on the value of the COPs. Quoting Desmond Tutu’s self-classification as ‘a prisoner of hope’, Robinson observed that climate change won’t be solved in the lifetime of anyone alive today, not even the newly born. It will be a life-long project for us all. This is a daunting thought, but, Robinson added, climate action also provides meaning, existential meaning, to one’s life – and that’s what people most crave. Climate action gives us purpose.

And so, despite the discomfort and setbacks, the Blue Zone remained occupied by so many ‘prisoners of hope’, all struggling to secure a safe and prosperous future for human and non-human life.

Towards a global mutirão

The ambition was a global mutirão, an Indigenous concept that refers to collective effort in pursuit of a common goal.

Yet to reach agreement within the multilateral process of the UNFCCC, hope had to take another hit at COP30. There was significant support for two roadmaps, one to phase-out fossil fuels and another to end deforestation, each backed by about 90 countries. However, neither made it into the final deal – with Brazil pledging to continue advocating for the roadmaps for the remainder of its COP30 presidency. The petrostates kept out any mention of 'fossil fuels'. Countries did agree to triple funding for adaptation from developed to developing countries, but the goal of roughly $120b a year was pushed back five years to 2035.

But multilateral negotiations are only one strand of COP30. Brazil’s flagship initiative, the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), was launched earlier with $5.5b is pledged. The largest contribution ($3b) came from Norway, with $1b each from Brazil and Indonesia, over $500m from France, and an unspecified commitment from Germany. This falls short of Brazil’s $10b target for COP30, but at least validates the willingness of funders to invest into forest stewardship. Further economic modelling is needed, in my view, to boost confidence that its novel structure will deliver returns without undue risks.

This was supplemented by a number of other smaller declarations and announcements, including (and by no means limited to) a work programme on harmonizing sustainable finance taxonomies, a coalition on compliance carbon markets, the Belém Declaration on Fertilizers to reduce associated emissions, a world-first coalition on information integrity to tackle climate disinformation, a $250m allocation to the Loss and Damages Fund, and the Intergovernmental Land Tenure Commitment to broaden protection of land rights for Indigenous peoples, local communities and Afro-descendant communities.

Promisingly, the Brazilian presidency also introduced the COP30 Action Agenda, a framework of thirty climate-related objectives, each with its own activation group to work across COPs. An area within the Blue Zone was dedicated to advancing this agenda through discussions among policy makers, finance, business, and civil society, often joined by Brazilian ministers and officials who kept participants focused on action. These cross-sectoral initiatives are where the most rapid progress might be made, free from the need for unanimity that constrains multilateral negotiations. Through plurilateral commitments, it is possible to make progress when not everyone is on board, then to expand participation over time by scaling up what works. This procedural innovation reinforced Brazil’s claim of COP30 as the ‘Implementation COP’.

Other labels, such as the ‘Nature COP’ and ‘Indigenous COP’, proved more contentious. To be sure, COP30 decisively bridged the divide between nature and climate change, overcoming the long-standing compartmentalization of these interrelated issues. COP30 also succeeded in attracting a large contingent of Indigenous peoples, especially from the Amazon region. However, presence is not the same as participation, and Indigenous representatives were more visible in the side events than the main negotiations. Munduruku people from the Amazon's lower Tapajós region chose to protest, blocking then storming the entranceway. This resulted in the militarization of the Blue Zone, an overt expression of state power. Yet the murder of Vicente Fernandes Vilhalva only a few days later, an Indigenous Guarani Kaiowá leader and land defender in southern Brazil, was a tragic reminder of the state’s failure to deploy that same power to protect communities and forests from ranchers.

Without a doubt, deforestation is declining dramatically under Lula’s presidency, a major turnaround from the Bolsonaro years. However, the laws to protect forest ecosystems are far from being fully enforced: the Amazon still lost 5,796 km² of forest in the year to 2025. Only weeks before COP30, Lula also swung behind Petrobras to authorize oil exploration off the coast from the Amazon river delta, a jarring contradiction with COP30’s veneration of nature.

As a leftist populist, Lula is exceptional in his ability to frame climate change as a problem for the masses, as a material threat to the wellbeing and economic security of ordinary people. His rhetoric is backed by consistently high levels of public concern among Brazilians. But, for Lula, as for many unionists of his era, jobs trump environment. This does not negate Brazil’s genuine progress on climate action, but it does illustrate the lumpy, contradictory nature of today’s transitions. The flow of climate-aligned capital isn’t yet crowding out investment into fossil fuels and agricultural intensification. Until it does, the politics of climate change has the hard job of straddling the old system and the new.

A multipolar COP

If this COP deserves any other name, it is perhaps the ‘Multipolar COP’.

President Trump’s re-election is both a symptom and an accelerant of the decline of U.S. hegemony: his constituency is fuelled by resentment over the loss of American economic advantage, yet his trade and international policy is destined to aggravate that very same problem. On the issue of climate change, his administration has opted for obstructionism (like recent bullying tactics over maritime emissions) and retreat (like Trump’s withdrawal again from the Paris Agreement). This creates space for others to lead.

(1) Fans to beat the heat. (2) President Trump: absent but ever-present at COP30. Author's photos.

This multipolarity was highly visible in Belém. Brazil, a founding member of the BRICS coalition of emerging economies, revelled in its leadership of the COP30 presidency. China and India sent large delegations to Belém to project their strategic interests in the global transition to net-zero. Both these countries, as net energy importers, have less to lose from decarbonization and potentially much to gain. This is most obvious for China which has already established global supremacy over the manufacturing of solar panels, EVs and batteries. India is apparently plotting its own technological breakthroughs, including leveraging its capabilities in digital public infrastructure. The BRICS are all large markets and increasingly interdependent: President Lula successfully lobbied for BYD to establish its first EV production plant outside of China in Brazil. Only Russia, an unrepentant petrostate, has little invested in the climate agenda, but it contributes to multipolarity too by violent aggression and tactical destabilization.

This fragmentation of interests is also occurring within the U.S. itself, as some states choose to defy the federal government on climate action and other issues. Trump refrained from sending an official delegation to Belém, yet over 100 U.S. leaders and officials travelled to Brazil, organized by America Is All In, Climate Mayors, and the U.S. Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition of 24 state governors that represent 57% of the U.S. economy. Free from Trump’s mischief, this economic bloc probably fared better than it might have otherwise. California governor Gavin Newsom used his COP30 trip to establish direct partnerships with Brazil, Colombia and Chile. It is a reminder that trading nations make a mistake by treating the U.S. as identical to the oil-producing states that supported Trump’s path to power. The U.S. is rather a highly variegated market that includes blue states along both coasts that have enduring climate commitments, less aversion to global trade, and large populations of conscientious consumers who are willing and able to buy EVs, solarize their homes, and shop at Whole Foods for deforestation-free, nature-positive produce.

The American social scientist Elinor Ostrom argued that climate governance is inherently polycentric, a system of leadership and followership that occurs at multiple levels and locations. A loss of ambition in one part of the system does not necessarily mean a reduction to total ambition, because other entities may step into the gap, seeing opportunities to seize or duties to fulfil. Consequently, we shouldn’t focus only on multilateral efforts, rather we should encourage efforts among diverse actors at multiple scales (which the COP30 Action Agenda rightly does). On this view, the current fragmentation of climate politics is not an aberration, rather a revealing of its true nature.

It is also a matter of circumstance. At the Business and Finance Forum, one of many pre-COP events in São Paulo in early November, BloombergNEF’s CEO Jon Moore explored the frame of different paths, different speeds to make sense of the uneven distribution of climate progress. Running through country-level data, he showed how countries had highly divergent starting positions and, therefore, unique challenges to decarbonize. Compare, for example, Brazil with South Africa, the former with an 88% share of renewables in electricity generation, the latter only 13% with a heavy dependency on coal. This poses distinctive risks and opportunities for each country, and no single pathway to net-zero. As a case in point, Brazil is already positioning itself as a source of clean energy for the hyperscalers and their energy-hungry data centres, turning its low-emissions grid into a global competitive advantage.

From the Amazon to Godzone

What might New Zealand take from all this?

Firstly, in developing a strategy on climate change (and other outward-facing matters), we need to reckon with our increasingly multipolar world. Climate action is no longer only about our moral duties to developing countries; it is also about aligning our interests to the industrial strategies of developed and emerging economies. Our choice over allegiances, over whom to follow or endorse, is critical.

Do we protect the interests of the petrostates, because this is the path of least resistance for our own fossil-powered patterns of consumption? Do we electrify our economy and therefore accept a greater dependency on China and others for the electrotech they export? Do we endorse the EU as the global standard-setter and continue to jump its regulatory hoops to retain market access? Do we exert our own leverage on the BRICS and other emerging economies, only engaging in trade and knowledge transfer when it supports the Paris Agreement and other environmental and human rights frameworks?

We can muddle along only so far by trying to please everyone, because these are material choices that create winners and losers. For example, a shift to EVs entails an economic loss to producers of ICE vehicles, liquid fuels, and all the associated infrastructure; but weak ambition on climate policy entails an economic loss to EV-producing nations because it protects the arbitrary market advantage of incumbent technologies like petrol vehicles. There is no neutral position: it is a question of interests through and through. We must choose whose economic opportunity to frustrate, and which of our national interests to advance.

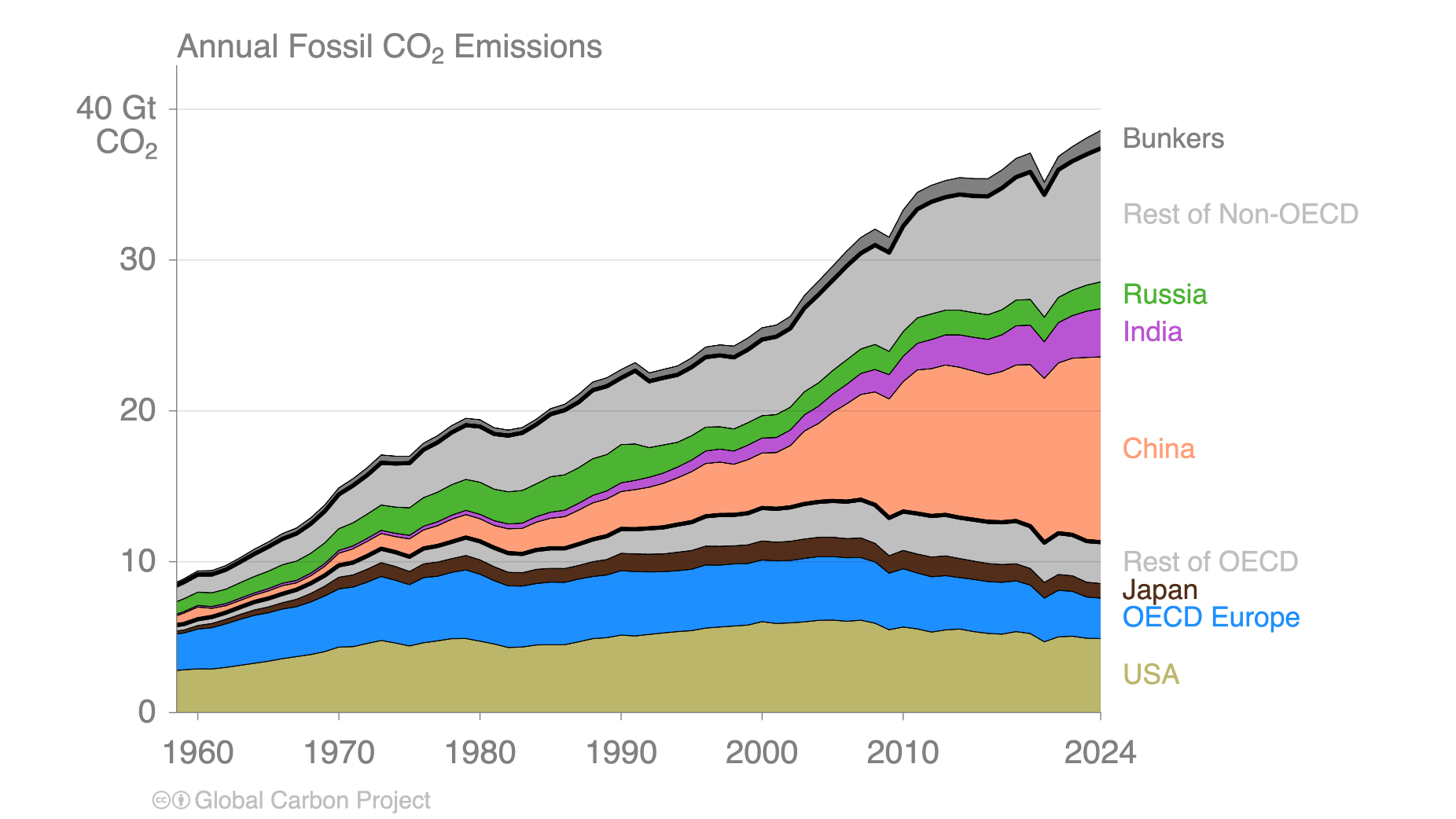

Secondly, we should think more carefully about New Zealand’s relationships to the emerging economies, especially through the lens of global innovation processes. These are vast and growing markets with complicated, ambivalent positions on climate action. But there are elements of ambition, not only because countries like Brazil and India are disproportionately exposed to the impacts of climate change, but because global mitigation pathways create opportunities for leadership in a new global order. If climate solutions are successfully deployed in these economies, the scale of avoided emissions is enormous (the BRICS already account for 41% of global CO2-e emissions). New Zealand has significantly diminished and disordered its research and innovation sector over the last two decades, yet we still have residual capabilities as an ‘innovation nation’. We are also an ideal testbed for climate solutions that, once proven in our well-regulated domestic market, can be profitably scaled up offshore. There is a clear alignment of interests in helping emerging and developing economies to leapfrog ahead to Paris-aligned development pathways.

In the case of Brazil, those opportunities are most acute in agriculture, forestry and land use. Thanks to Brazil’s place in the global imagination and the entrepreneurialism of its climate leaders, there are already billions of dollars of private and blended capital allocated for nature-based solutions, like reforestation and regenerative agriculture. If agritech and nature tech can help to deploy that capital most effectively, it stands to gain a foothold in these major markets. If New Zealand fails to contribute to this process, we’ve seriously missed a trick.

Which brings me to my third and final thought: New Zealand needs to learn from other countries how transitions are occurring in the real world. We need to be more sceptical about unproven academic theories on spontaneous market forces, and to observe the way that markets are actually being mobilized through directed innovation. China is the obvious exemplar here, emerging as an electrotech superpower through deliberate industrial strategy. But Brazil is learning this lesson too: at a COP30 discussion on land use and biodiversity, I listened to a Brazilian expert observe that industrial policy had got Brazil into its current predicament on deforestation, and only industrial policy would get it out. My glimpse of the innovation emerging in Brazil – from environmental measurement to financial structuring to land use practices – was humbling.

New Zealand is very different to both China and Brazil, yet, as a matter of historical fact, our land-based economy evolved through a similar process, with market forces swinging in behind state-directed decisions over land clearance and exotic pine plantations. Knowing what we know now, the state might mobilize market forces in the direction of long-term value creation, rather than cheap extraction. In agriculture and forestry, and other areas like geothermal energy, New Zealand has hard-won advantages that we could be exporting to the world, addressing the climate challenges of larger markets by way of addressing our own. COP30 revealed that, while some parties are conspicuously backpedalling on climate action, others are forging ahead. New Zealand, by contrast, seems to be on the sidelines, increasing our dependency on imported solutions and neglecting the economic opportunities in generating our own.

New Zealand should embrace Brazil’s call for a global mutirão, but if being so high-minded is too difficult, we might also start acting in our own long-term national interests. Transformative change is already underway – and we should be aiming to minimize the downsides and maximize the upsides. Climate action is increasingly material and geopolitical – and there is no going back.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future essays like this, as well as other updates and transition-related briefings.