In this week's edition of The Pointillist, a focus on sustainable finance with new research on climate risks, green bonds, disaster-fuelled growth, planetary solvency, Wall Street's retreat from climate posturing, and more.

It was confirmed last week that BlackRock has bailed from its $2 billion clean tech commitment to New Zealand.

Launched in August 2023, the deal was described by then-Prime Minister Chris Hipkins as 'a watershed moment'. At the same time, however, Brett Christophers, author of The Price is Wrong, in a Q+A interview with Jack Tame, offered a more sceptical assessment:

The thing is the money's not there yet... they'll establish the fund, but they have yet to go on the road, so to speak, to raise that capital. And while they're doing that, there'll be ongoing discussions with the New Zealand Government... Renewables investment, everywhere in the world, is a risky business. BlackRock, like other leading private sector investors, does not invest in renewables unless it has seen that a significant amount of that risk has been absorbed by other actors. So they will not have said we're going to give you this money without the government giving some form of assurance that there'll be a scheme in place whereby some of that risk will be removed.

The Sixth Labour Government might have offered assurances, but these did not survive the 2023 general election. The current Coalition Government is not in the business of derisking renewable energy (see why investment into offshore wind withdrew from New Zealand), even while it uses the Crown balance sheet to derisk gas exploration, new thermal firming, and a proposed LNG terminal. And so this 'watershed moment' ultimately didn't hold any water – but what lessons (if any) will policy makers take from this?

Another aspect of this story is the great walkback on climate finance, particularly in the United States. This analysis by the New York Times is illuminating:

The story of how Wall Street turned its back on climate change — how a bold attempt to transform finance collapsed — began almost as soon as Mr. Fink and his allies announced their ambitions to use capitalism as a tool to save the planet. Republican politicians joined conservative activists, including groups funded by the fossil fuel industry, to engineer a sweeping pushback at what they saw as corporate America’s attempt to advance liberal policies. Their tactics involved filing lawsuits, passing laws, pulling funds out of Wall Street accounts and using social media to tarnish the reputation of individual executives, including Mr. Fink... Republican legislatures around the country introduced more than 100 bills to penalize financial companies that supported E.S.G. practices. Republican state treasurers around the country began pulling money out of BlackRock. By the end of the year, conservative lawmakers in Texas had opened investigations into BlackRock and other Wall Street firms for their climate commitments and E.S.G. practices, and Republicans in Congress had subpoenaed G.F.A.N.Z., BlackRock and State Street.

This is a vivid case study of climate obstructionism (which I discussed in the previous edition of The Pointillist #5). Of course, there are lessons to be learned about how to advance climate finance more strategically. But we should also not be naive about the role of organized resistance, not because climate finance is unworkable in general, rather because some specific people have a lot to lose.

On a brighter note, the fickleness of the big gorillas of global capital – their susceptibility to influence from litigation, social pressure and political manoeuvring – suggests that they could easily turn again. After all, beneath the surface, the hard realities of climate change are not invisible to financial sector actors...

Concerns about climate-related risk are shaping present-day financial decisions. The Central Bank of Ireland just released a report on the risk of flooding on the credit conditions of non-financial firms. The report finds that loans to borrowers in flood-prone areas face an interest rate premium of roughly 7 to 13 basis points, and are 4–16% more likely to provide a collateral. Consequently, the Bank warns of a 'financing retreat' ahead:

While this [research on flood-prone areas] indicates that Irish lenders are effectively pricing in this source of risk, this might prove to be detrimental for borrowers located in such areas and the issue is expected to worsen in the coming years.

The financial economy isn't only factoring in the physical risks of climate change, but also the transition risks associated with climate action. The European Central Bank (ECB) recently published a working paper, Climate change, bank liquidity and systemic risk, which empirically demonstrates that transition risk is already being treated as financial risk:

This paper examines how climate transition risks — particularly banks’ exposure to carbon intensive borrowers — affect short-term funding costs in the European repo market. The repo market is the backbone of bank liquidity and a core channel for transmitting central bank policy rates. It is generally considered one of the safest financial markets, given the short maturities and collateralized nature of transactions.

Our findings show, however, that even here climate risks are priced in, with meaningful consequences for financial stability and monetary policy. Using transaction-level data from 2019–2022, we combine information on European banks’ repo borrowing with data on their “financed emissions,” that is, the greenhouse gas emissions of the firms they lend to. We find that banks with higher financed emissions consistently pay higher borrowing rates in the repo market. Quantitatively, a one standard deviation increase in financed emissions translates into repo rates that are 7–12% higher, on average. This “carbon premium” cannot be explained by usual drivers of repo pricing, such as collateral quality, transaction maturity, or counterparty relationships. To understand why this premium arises... our evidence points to a mix of both a risk premium and what we term an“inconvenience premium,” reflecting the reluctance of climate-committed banks to extend cheap funding to more carbon-exposed peers.

We also assess the broader implications. First, the carbon premium amplifies during times of market stress, tripling in size. This suggests that climate risks interact with existing vulnerabilities to heighten systemic risk. Second, transition risks alter the transmission of monetary policy: repo rates for high-emission banks adjust more quickly to central bank rate hikes, indicating uneven pass-through across the banking sector. In sum, our study provides the first evidence that climate risks affect the pricing of bank liquidity in Europe’s core funding market and highlights how climate transition risks can amplify financial fragilities and interplay with monetary policy transmission.

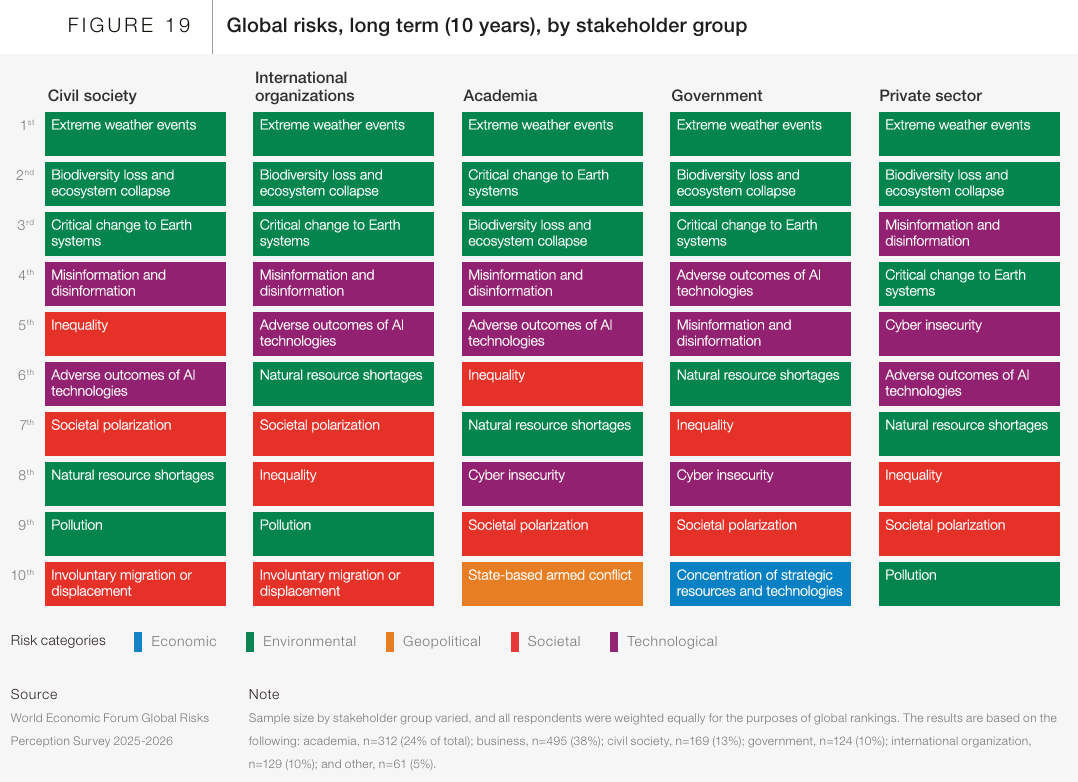

An acknowledgement of climate- and nature-related risks persists among global decision makers, as demonstrated by the new edition of WEF's Global Risks Report 2026 (see figure below). Environmental risks are prominent among all stakeholder groups – with the private sector rating extreme weather events, and biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, as the top two long-term global risks.

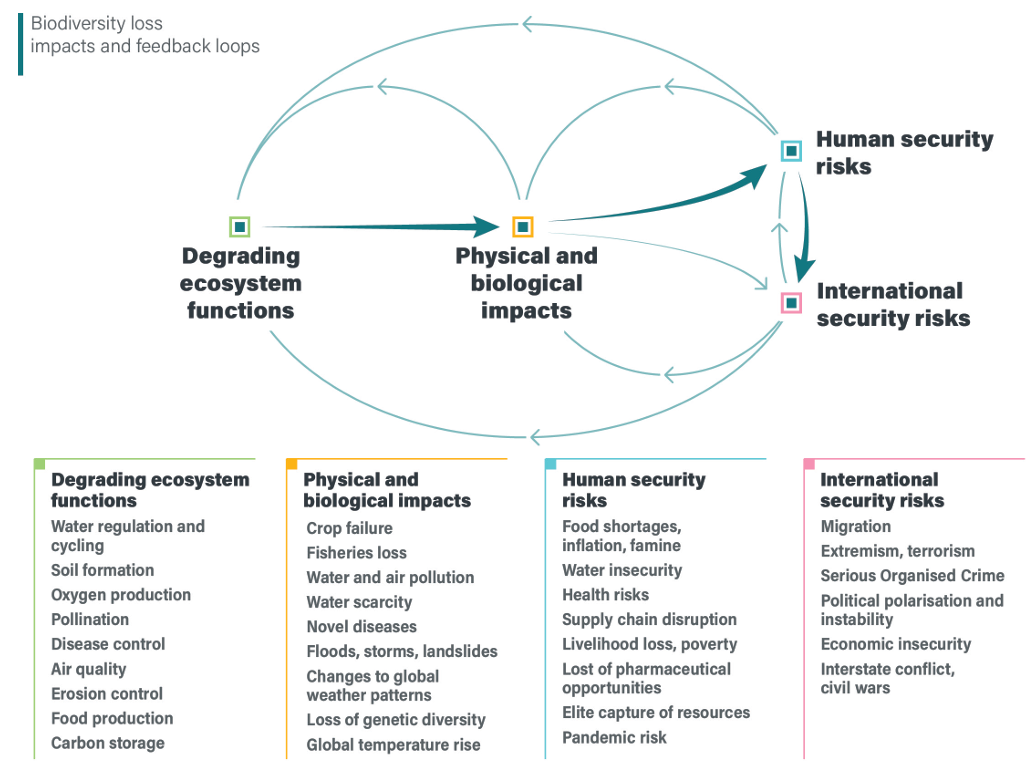

This national security assessment from the UK's Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs also emphasises the flow-on effects of environmental risks, which threaten to cascade into security risks at the personal and international levels.

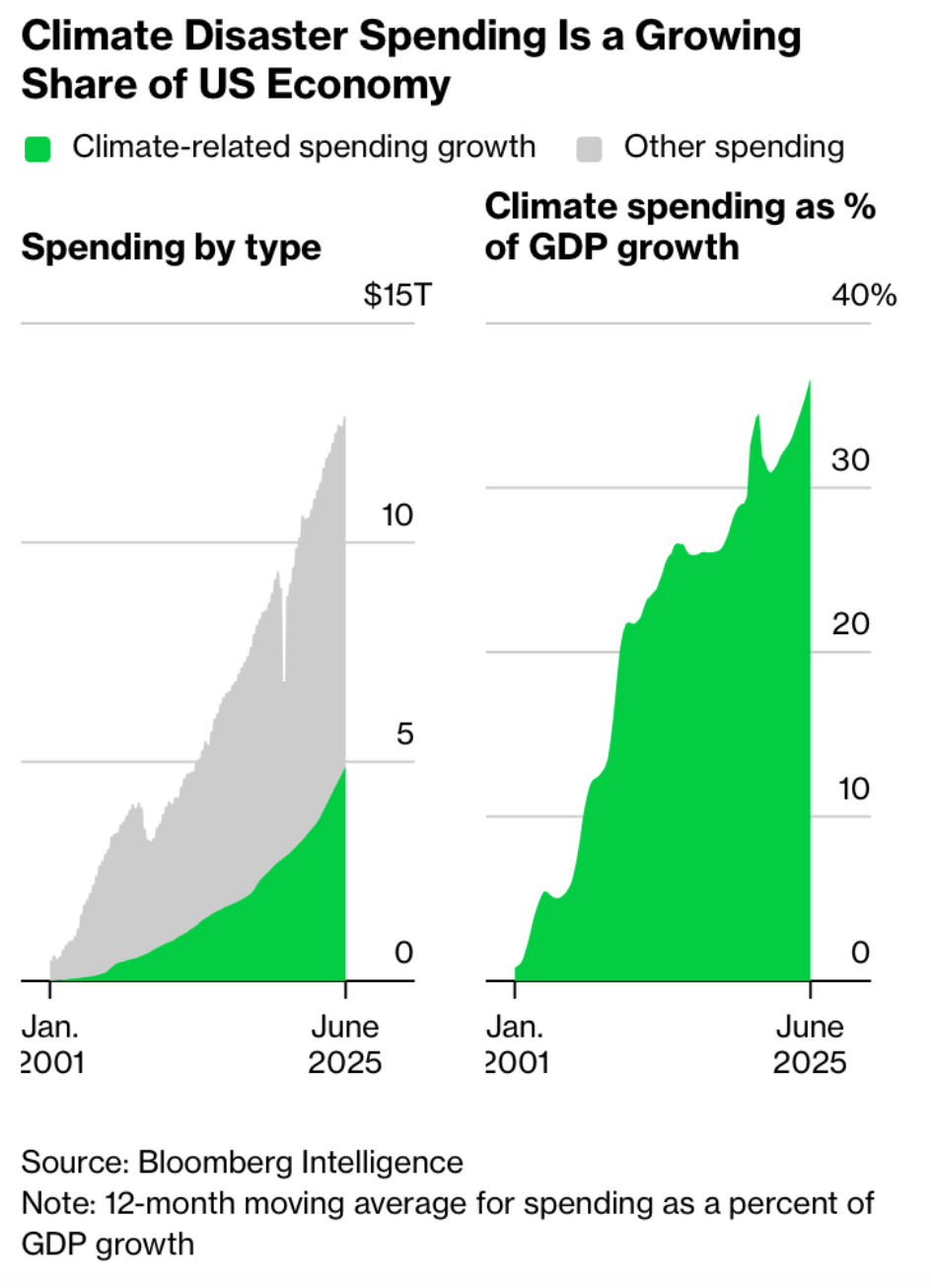

Yet from a macroeconomic perspective, climate-related damages are not only associated with economic losses, but also (not unlike the economics of war) bursts of economic stimulation, especially during the recovery phase. This Bloomberg story tracks the growth of the 'disaster industrial complex' in the US:

Weather disasters like Helene are becoming both more frequent and more severe because of climate change. Although they blow over fast in physical terms, the economic impacts play out slowly. It takes three to six months for survivors’ insurance checks to land, at best; maybe three years for federal reimbursements to cash-strapped localities to drip out. The result is that the US is now always paying to recover from disasters, and this is contributing a larger and larger share of GDP growth. The US economy has grown by $20 trillion since 2000, to $29 trillion last year. About $7.7 trillion of that — or 36% of all the growth in GDP — is spending related to recovering from or preparing for disasters… The country spent almost $1 trillion in the 12 months ending in June, money that most everyone would prefer to spend on goods or services of their choosing. In the 1990s, the annual average was closer to $80 billion in current dollars. Government spending on disasters, and companies leading the recovery, make up an underappreciated, yet major, slice of the US economy. The money goes to insurers and waste haulers, power grid equipment manufacturers and engineering contractors, hardware stores and self-storage facilities. These are good businesses to be in in challenging times.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2025-disaster-industrial-complex-us-economy/

Incidentally, this is one reason I am wary of crude versions of degrowth, which take declining GDP to be a desirable economic goal. As we know from the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquake sequence, post-disaster rebuilding can increase GDP significantly, but this would be an appalling reason to deny investment. Similarly, it would be ghoulish to underfund regions like Tai Rāwhiti and Tai Tokerau after extreme weather events because of some squeamishness about the economic stimulation. If rising GDP is an unreliable measure of aggregate wellbeing – which it surely is – then why wouldn't declining GDP be too? It is like mistaking the compass for the journey.

This is clever research by Benjamin Schneider, which tests the hypothesis that green bonds are effective signalling devices that express the issuer's commitment to climate action and reduced climate risk exposure. Schneider examines the impact of green bond issuance on the issuer's outstanding bonds and equity:

The results reveal a consistent pattern: after green bond announcements, equity valuations rise and yields on outstanding bonds fall, relative to matched conventional bond announcements. Yield effects are strongest at longer maturities, consistent with the view that climate risks are expected to materialize over the long term and that green bonds reveal climate-related information.

These effects are most pronounced for non-financial over financial firms, and lower- over higher-rated firms. Schneider also finds that green bond issuers have lower stock return volatility during spikes in climate-related concern. A short summary of the paper is below:

A new report, Parasol Lost: Recovery plan needed, by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries and University of Exeter. It advances the concept of 'planetary solvency' – that is, managing human activity to minimise the societal disruption from the loss of nature's critical support services. Failing this, the report warns of a potential 50% drop in GDP later in the century. Consequently, the report calls for a 'planetary solvency recovery plan':

Finally, the Financial Markets Authority (FMA) has published a kaupapa Māori research report, He Kākahu Whenua: A case study of Toha Network and East Coast Exchange, which explores innovation in the Māori economy.

Full disclosure: I am a co-founder of the Toha Network, so I am unavoidably biased in encouraging you to take a look.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future content like this, as well as essays and transition-related briefings.