In this week's edition, a focus on systems thinking and the social dimensions of transitions, including obstructionism, inequality, backlash, supply chain solidarity, regenerative agriculture, and more.

Anyone familiar with Donella Meadows' leverage points will know that paradigms, or worldviews, offer the deepest leverage for change. But Meadows only gives broad-brushstroke guidance on how to change paradigms, and doesn't dwell on the challenge of navigating multiple worldviews in diverse societies.

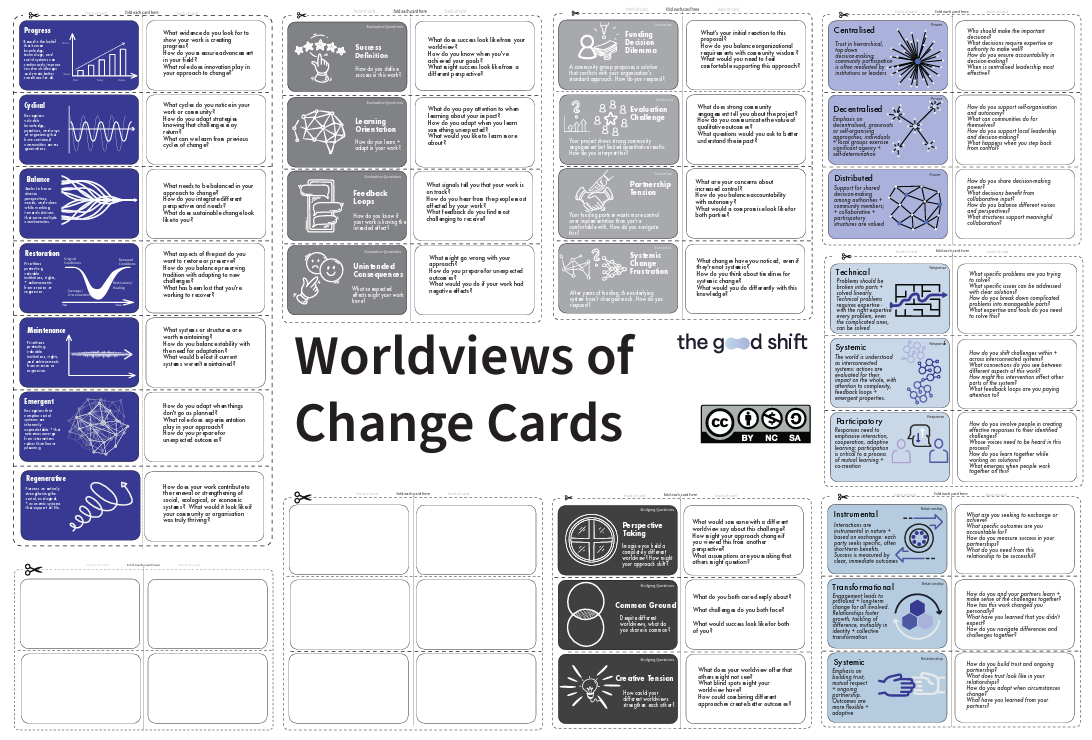

The Good Shift, led by Ingrid Burkett, has produced a useful guide, Surfacing Worldviews of Change, for advancing change within diverse groups. Designed for systems practitioners, it includes a set of printable cards to facilitate group dialogue.

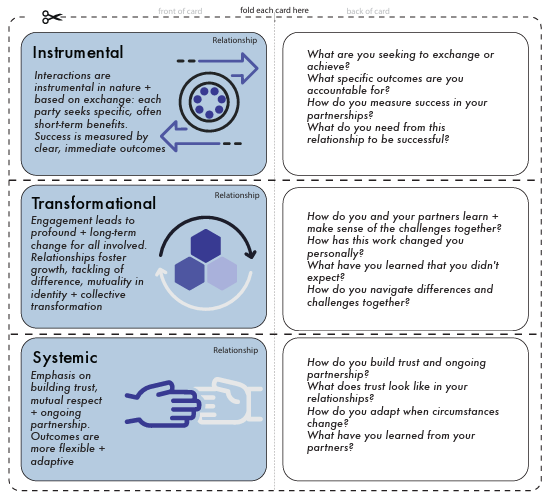

Participants can use the cards to locate and to interrogate one's understanding of change as progress, restoration, cyclical, maintenance, balance, emergent or regenerative. Other cards explore common paradigms of power, response, and relationships (below).

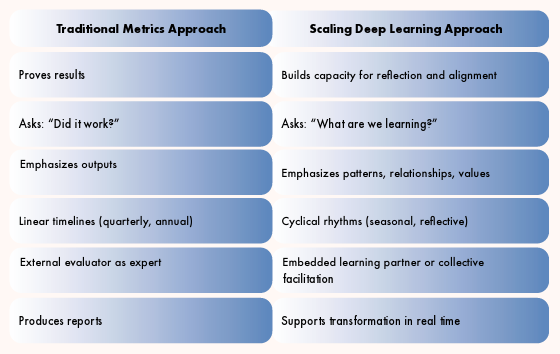

In a similar vein, Scaling Deep by Systems Sanctuary explores what types of measurement actually matter for systems change. In contrast to the instrumentalist logic of 'what gets measured gets managed', the report proposes 'learning infrastructure' for 'cultivating living ecosystems of relationship, reflection, remembrance, and renewal':

One section that resonated for me was about 'the importance of decentering funders in learning spaces' – which is relevant for corporate, government and philanthropic funders:

True systems transformation is relational, distributed, and emergent. Often, when funders are leading learning initiatives, peer learning risks becoming performative rather than authentic. Evaluation collapses into compliance rather than generative reflection. Funders, even with good intentions, may inadvertently shape agendas and what is valued—narrowing what is seen as credible change. Communities often contort their strategies to fit funder logics or timelines, sidelining the deeper, relational approaches that true systemic change demands.

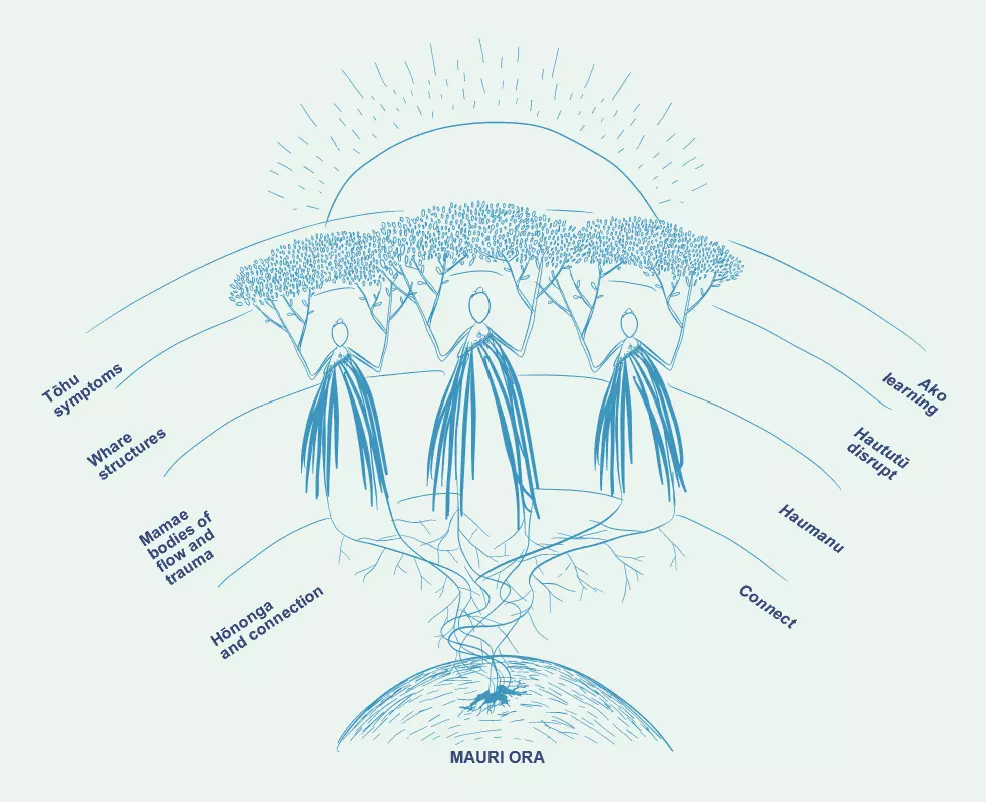

One of the global case studies in the aforementioned report is Haumanu, an emerging approach to restorative systems change that draws from mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge (convened by Aotearoa's Centre for Social Impact). It treats the healing of collective trauma as a foundation for systems change.

Working upwards from the objective of mauri ora (or wellbeing), the challenges on the left are addressed by the actions on the right. Thus, once a group is formed through connection (hōnanga), the group moves to restorative actions (haumanu) to address pain and trauma (mamae). Only then is it safe to induce systems change through the disruption (haututū) of institutional structures (whare). Adaptive learning (ako) is threaded throughout the process.

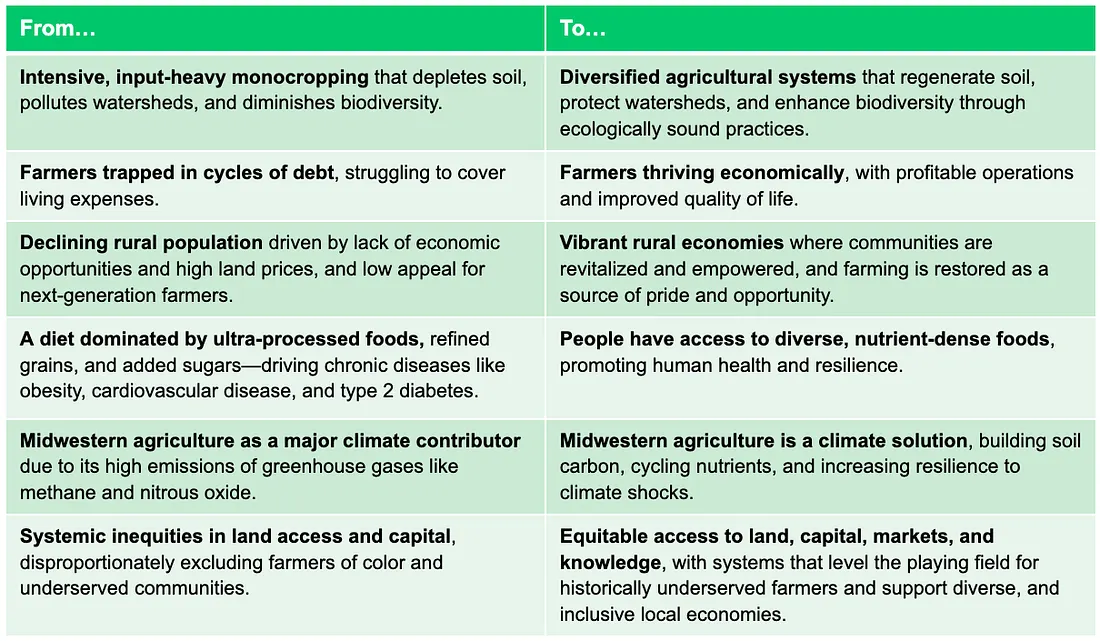

Turning to systems thinking in sustainable finance, I am enjoying the reflections from TransCap Initiative on its regenerative agriculture initiative in the U.S. Midwest. Andre Ticoulat argues that, as the logic of agricultural management transitions, so must the logic of finance:

The approach that TransCap Initiative is taking is capital orchestration, which realigns the instruments of finance to the complex, ecological nature of regenerative agriculture. If you want to learn more about this approach and the underlying concepts, this report, Definition and Hallmarks of Systemic Investing, is a good place to start.

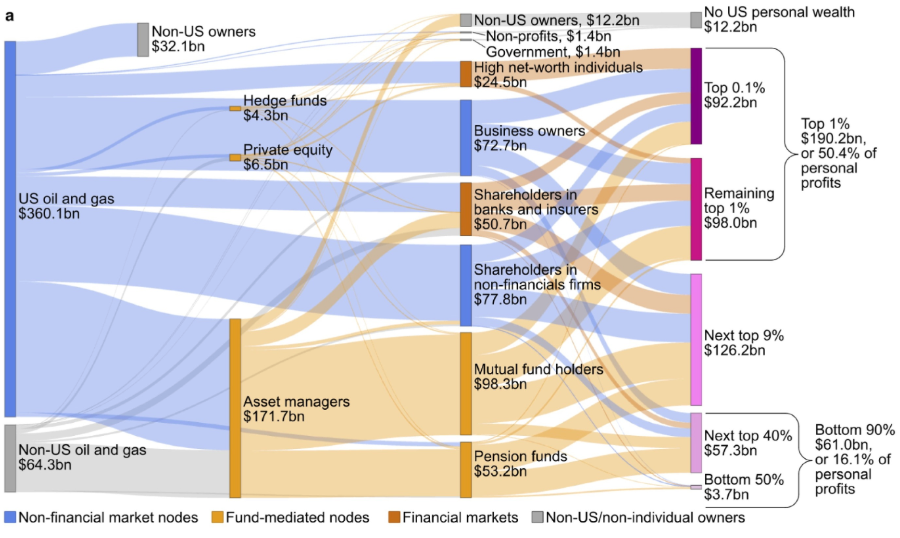

It is no real surprise that, in an unequal society, the spoils of the fossil economy are distributed unequally to those with the most economic power. However, to see it mapped out is something else (from Semieniuk et al. 2025).

An interesting paper from Patrick Bayer and Federica Genovese (blog version here; academic version here) which explores regional attitudes to climate change policy in the U.K., specifically in Yorkshire, Wales and Scotland:

Our findings suggest that declining carbon-intensive regions are neither inherently nor homogeneously hostile to climate cooperation. Their attitudes are conditional: when they distrust national elites or feel bypassed by decision-makers, scepticism grows; when they trust regional institutions and see credible pathways for representation, support for climate action increases...

This underscores a critical policy lesson. The legitimacy of climate cooperation... hinges not only on economic support packages or technological solutions, but also on institutional trust and regional political voice. Strengthening devolved communities, ensuring meaningful regional participation, and demonstrating responsiveness to the specific challenges faced by vulnerable communities can help build the social foundations for a durable green transition.

These findings are worth contemplating in the context of Aotearoa, especially to counter the pessimistic narrative that the regions necessarily see net-zero transitions as an economic threat. Through the lens of this research, Taranaki's initial resistance to the surprise suspension of offshore oil and gas permits in 2018 might be interpreted as a reaction to 'an elite-driven, externally imposed burden', not necessarily a rejection of climate action tout court. Looking ahead, we might also worry that the conditions for regional resistance will be exacerbated by the gutting of regional leadership capacity through local government reforms. These are liable to increase the regions' exposure to policy edicts from central government, and also to undermine the capabilities of regional institutions to proactively and directly engage in the economic opportunities that arise from climate cooperation and global transitions.

The Climate & Community Institute has released its Supply Chain Solidarity Principles. These attempt to walk the delicate line between the need for an energy transition and the unavoidable impacts of mining on ecosystems and communities. Accordingly, the principles extend a duty of care along the supply chain of batteries and other technologies – with commitments to oversight and democratic accountability, environmental protection, dignified work, collective benefit, and more.

The launch of the principles was accompanied by this short film:

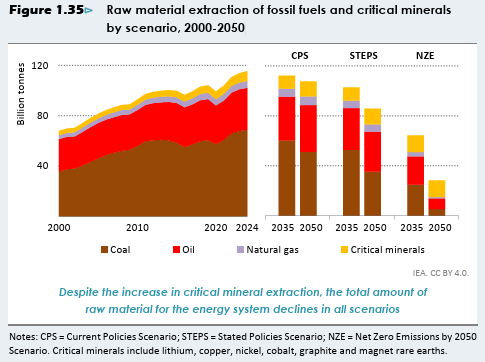

It is worth noting that the overall requirements for raw materials are substantially lower for a renewable energy system than a fossil fuel system. The chart below is from the recent World Energy Outlook 2025 by the International Energy Agency (IEA). It shows that global demand for critical minerals increases in the Paris-aligned Net Zero Emissions (NZE) Scenario, but this is more than offset by the reductions to coal and oil extraction.

Still, as I've argued before, 'just because renewables are less resource-intensive overall, this is no excuse to ignore these issues entirely'. Improving the supply chain for lithium and other critical minerals is vital for defending the public legitimacy of the energy transition.

Climate backlash and policy dismantling are emerging themes in the academic literature on sustainability transitions (e.g. Schaub et al. 2024; Patterson et al. 2025; Bosetti et al. 2025). This is an example of academic theory chasing after reality as various countries face setbacks in their net-zero strategies and plans, exacerbated by what is commonly described as the 'populist' turn in today's politics.

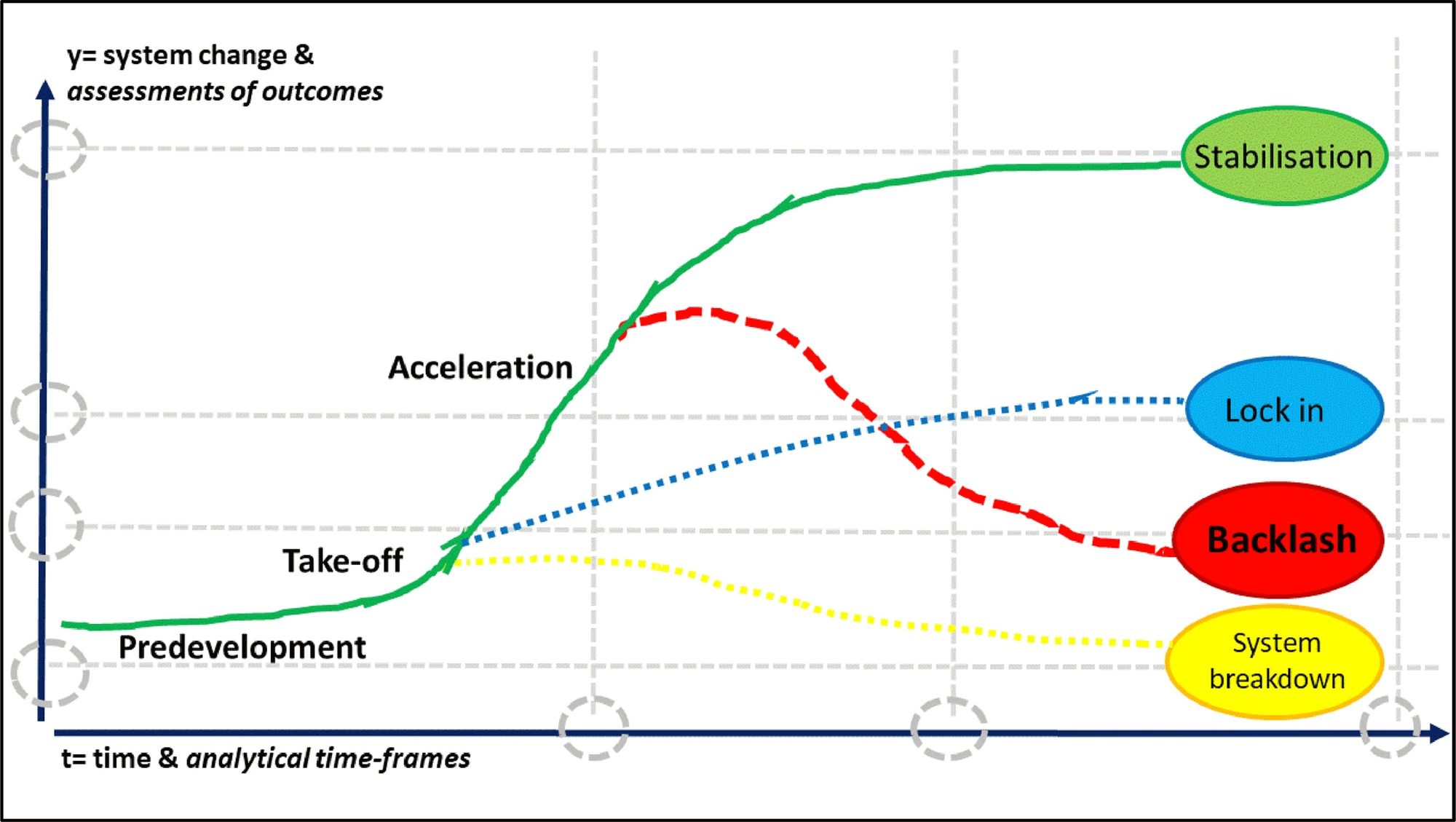

An early effort by Bonno Pel (2021) conceived of the different ways that transitions can 'fail' – from a lock-in that prevents new innovation from scaling (think New Zealand's current approach to EVs), to a backlash where innovation is actively resisted (think the Luddites), to a breakdown where the innovation is effectively eliminated (think Erewhon).

From a New Zealand perspective, this new paper on the Swedish experience (Förell and Fischer, 2025) is intriguing. In 2022–2023, Sweden's policy mix was substantially weakened in spite of the coalition government's rhetorical commitment to pursuing emissions reductions and upholding targets. The authors explain that this strategy was partly successful because of the coalition's 'discursive flipping', which involved appealing to a diverse range of liberal, welfarist and nationalist arguments for its policy reversals. This ideological fluidity appeared to disarm the opposition who were reluctant to criticize the rationale, even if they opposed the policy walkbacks. Unfortunately, the authors do not offer any antidote to this strategy.

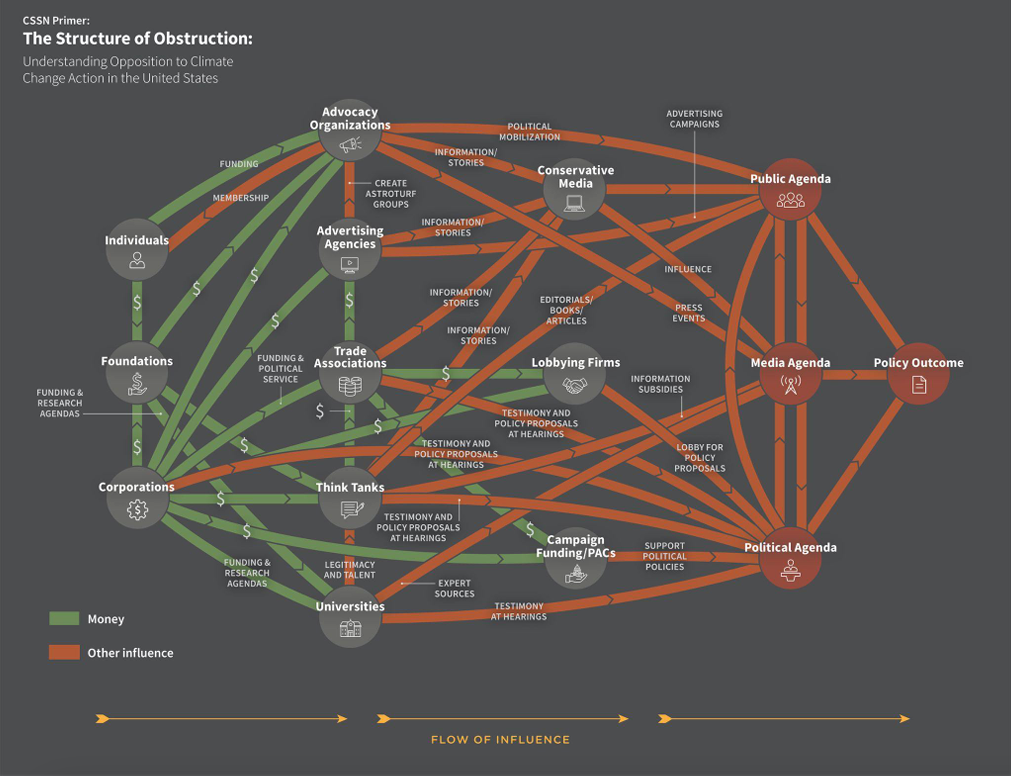

Finally, the Climate Social Science Network (CSSN) recently released Climate Obstruction: A Global Assessment, published by Oxford University Press, which is available as a free e-book (here).

The introduction captures a critical point:

The decades of insufficient action on climate change have often been explained by pointing to various barriers—human nature, uncertainties in the science, technical shortcomings of renewable energy sources, democracy deficits, neoliberalism’s emphasis on short-term economic logic, and deep religious and other cultural beliefs. [We] do not dispute the plausibility of these factors. However, based on the accumulating evidence documented here, we offer a different argument: while the major social transformation required to avert dangerous climate change was never going to be easy, it has been made exponentially more difficult by various forms of obstruction. Efforts to address climate change have been unsuccessful, we believe, because of the work to obstruct them and our failure to understand and overcome this obstruction.

This is an important corrective. Climate advocates have a tendency to castigate themselves for failures of communications or strategy, or to bemoan politicians or 'the public' for not caring enough. No doubt we'll see plenty of this in the lead-up to New Zealand's general election next year. But it is vital to be clear-headed about the role of deliberate obstructionism, to differentiate climate strategies that were defective from those that were blocked, and above all to identify who is obstructing climate action and why. Know your adversary!

Climate Obstruction has ten key findings:

- Climate obstruction is not just about denial, it is also about greenwashing, delay tactics, unviable techno-fixes, and misinformation.

- Big oil is a key player in obstruction, but only one of many – which can also include coal companies, utilities, car manufacturers, and agribusiness.

- Trade associations are key agents of climate obstruction by allowing corporations to 'hide in the crowd' when engaging in obstructive actions.

- Networks of think tanks are spreading obstruction globally.

- PR firms enable corporate efforts to obstruct climate action.

- Some governments have taken leading roles in obstructing climate action.

- Obstruction occurs within multilateral governance structures, including the UNFCCC.

- National and local contexts shape obstruction, particularly in the Global South.

- Obstruction starts at the top but requires social acceptance – from the media, political parties, politicians, and individual citizens.

- There are efforts to address climate obstruction through regulation, litigation, and social movements.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future content like this, as well as essays and transition-related briefings.