In this week's edition, the dilemmas of digital sovereignty, the gaps in demand-side policy for climate change, a new framing of batteries that historicizes their importance, and more.

To begin, a niche issue that touches on something much more significant…

The Law Association of New Zealand (LANZ) sent a letter this month to the Prime Minister and others to raise concern over cyber attacks and data breaches. In explaining these risks, however, the letter shed light on deeper dilemmas for New Zealand:

Overreliance on concentrated cloud and digital infrastructures creates centralised vulnerabilities with far-reaching cascading consequences… This is not only a consumer protection issue; it is also a competition, productivity and national security issue.

Data sovereignty is a growing concern among jurisdictions around the world. This is amplified by recent behaviour from the hyperscalers, most of them American, who have piled in on Trump’s America First paradigm, and sacrificed impartiality and trust in the process. Adam Tooze describes this as a ‘malign coincidence’, a marriage of convenience where disruptive economic and political forces are feeding each other to extract power and material gain.

The European Union has embarked on its EuroStack, a sovereign suite of digital infrastructures which encompasses cloud computing, connectivity, AI, chips and industrial policy. This builds upon, and extends, the earlier Gaia-X initiative for a federated data infrastructure.

But the EU is a supranational union with large pooled resources. Is a sovereign tech stack a viable option for a small country like New Zealand to replicate?

Perhaps a more plausible comparator is Canada. Yet Prime Minister Mark Carney has hinted recently that a ‘Canadian sovereign cloud’ will be part of his Major Projects Office (a new agency with similar objectives to New Zealand’s fast-track approvals legislation). Carney remarked:

This would build compute capacity and data centres that we need to underpin Canada’s competitiveness, to protect our security, and to boost our independence and sovereignty.

The Government of Canada (GC) also just released its framework for digital sovereignty, which it defines as:

... the ability of the GC to exercise autonomy over its digital infrastructure, data and intellectual property. It is the capacity to operate effectively and make independent decisions about digital assets, regardless of where technologies are developed, hosted, or supported.

New Zealand hasn’t really even begun this conversation (but hats off to Paul Selier from Catalyst Cloud for trying in his RNZ interview). But our government could do worse than follow these debates and simply swap out the word ‘Canada’ for ‘New Zealand’:

Cloud infrastructure from American companies, whether located in Europe or Canada, is incompatible with sovereignty. If Canada seeks genuine control over the physical and digital infrastructure that stores and transports information of its public, it cannot rely on US hyperscalers to provide it. These companies fall under US jurisdiction and, therefore, are subject to the 2018 CLOUD Act, which enables US authorities to access data they hold, even if that data is stored abroad. In other words, the US can access any data stored by American cloud providers in Canada without our authorization or even knowledge. This fact was confirmed by Microsoft, whose representative told the French Senate that the company could not guarantee that a French citizen’s data would not be transmitted to US authorities without the explicit authorization of French authorities. Hyperscalers’ claims about sovereignty, which often emphasize data localization and robust security practices while glossing over the US government’s ability to access information, risk being deceptive. [...]

No matter how we approach it, cloud sovereignty will be costly. Hyperscalers can offer more flexible and cheaper pricing models, and will likely be able to undercut emerging alternatives. To make digital sovereignty viable, the Canadian government will have no choice but to intervene, strategically investing in domestic cloud service providers and likely subsidizing these options. Energy is another crucial factor: cloud computing requires enormous amounts of power, and hyperscalers operate the largest and most energy-efficient facilities. The relative inefficiency of smaller Canadian providers will only drive up the cost of domestic options.

However, the costs of inaction are equally high. If Canada fails to invest in some form of sovereign cloud, we will continue to compromise our national security and lose the opportunity to capture value within the cloud computing market. Building sovereign cloud capacity would also position Canada to capture greater value in other digital markets, such as AI. Conversely, if the country further entrenches its dependence on US tech and fails to develop sufficient alternatives, those firms will be free to charge the government and the public whatever they want. Such profiteering will have long-term economic consequences that would likely outweigh the upfront costs of sovereign cloud development.

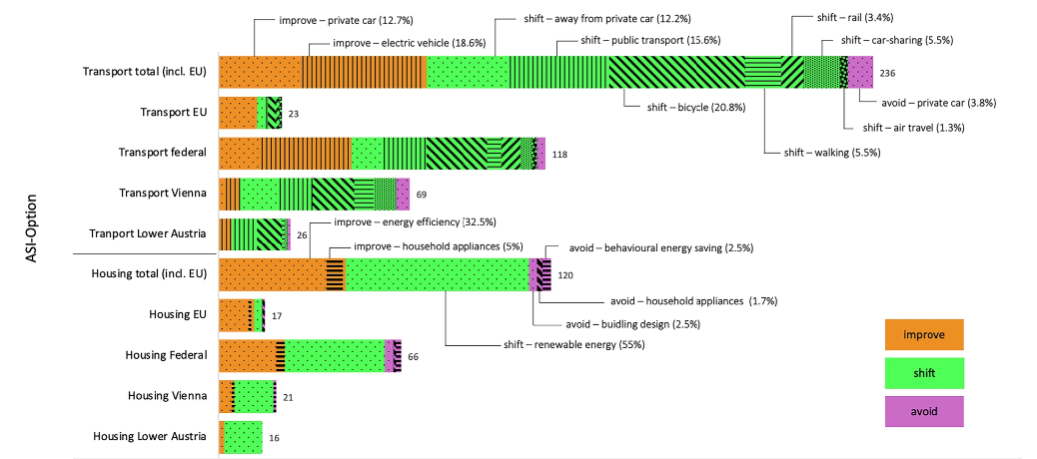

New analysis by Brad et al. (2025) on demand-side options in policy mixes. The literature on demand-side policy is growing, but this paper is notable for its assessment of actual policy implementation. With an analysis of 356 demand-side measures (!) in the EU and Austria, the paper shows that existing demand-side policy is stuck on improving and shifting consumption (orange and green in the bar chart below), but neglects avoiding consumption (purple).

This is a pity, because avoidance of emissions is the ultimate way to ‘buy us time’ to do the longer, more expensive work of decarbonization and technological substitution. In New Zealand, we've long spoken about forestry removals as our time-buying strategy, but this argument is ever more tenuous due to unresolved design flaws in the NZ ETS, the science of non-equivalence between forestry removals and fossil emissions, and the spectre of mitigation deterrence. However, avoided emissions really do ‘buy us time’. Every avoided flight or cruise ship holiday, every avoided commute by videoconferencing, every choice to prolong the use of existing infrastructure rather than replace it with high-emissions steel or concrete – these are gifts to the future that make mitigation pathways a little easier, the trade-offs a little gentler and, hopefully, our transitions a little more orderly.

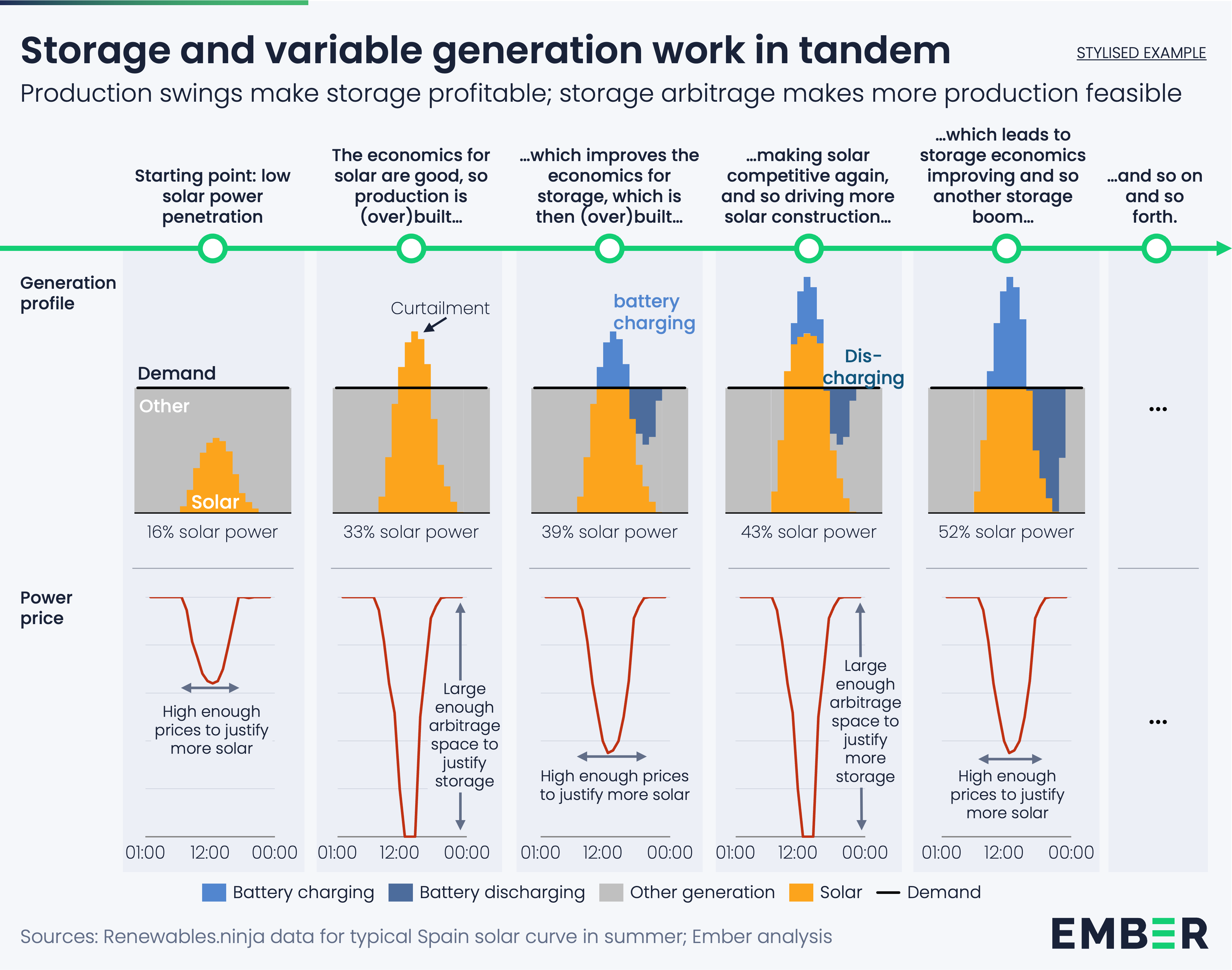

From the demand-side to the supply-side, batteries are emerging as the great unlock for the transition to renewable energy and end-use electrification. For systems thinkers, these are the buffers that stabilize a system by adding stocks to flows. In this case, battery storage are the stocks for firming the variable flows of electricity from solar and wind energy.

Daan Walter of Ember has nicely reframed battery storage as 'silos for solar', as akin to the granaries that accelerated the agricultural revolution:

Electricity is the ultimate perishable good; more so than grain, milk, or fruit, as it must be consumed within a fraction of a second. Producers race their output to market — literally at the speed of light — along copper wires, often oversupplying the system and driving curtailment and extreme price swings.

The rise of new electricity storage tech such as batteries addresses much of this challenge, just as previous storage technologies did. Grain silos stabilised harvests; refrigeration globalised fresh food. In every case, storage moved from rare and costly to cheap and ubiquitous. Electricity storage follows the same trajectory, turning the perishable into the persistent.

On this note, Australia recently became the world’s third-largest utility battery market. This is perhaps unsurprising, given Australia's extraordinary uptake of rooftop solar energy, which now powers more than 4.2 million homes and small businesses, and delivers 12.8 per cent of Australia's total electricity. This rapid influx of solar hasn't always been plain sailing, however, resulting in grid instability and controversial curtailments. But batteries are the 'silos' that the electricity system needs – and Australia is leaning in. The pipeline of battery projects jumped by 41 per cent in the year from August 2024 – from 109 GW to 154 GW. Meanwhile, the Clean Energy Council estimates that homeowners have cumulatively installed 271,000 home batteries, nearly double the total from 12 months ago. In Australia, the economics are very favourable: 'Installing rooftop solar can save households up to $1500 per year on energy bills, this almost doubles if you add a battery, with further savings available by joining a virtual power plant.'

Of course, New Zealand would do well to learn from this, to anticipate the looming flood of solar supply and invest pre-emptively in battery capacity. But this would require our institutions to be capable of what they are not – that is, to be strategic.

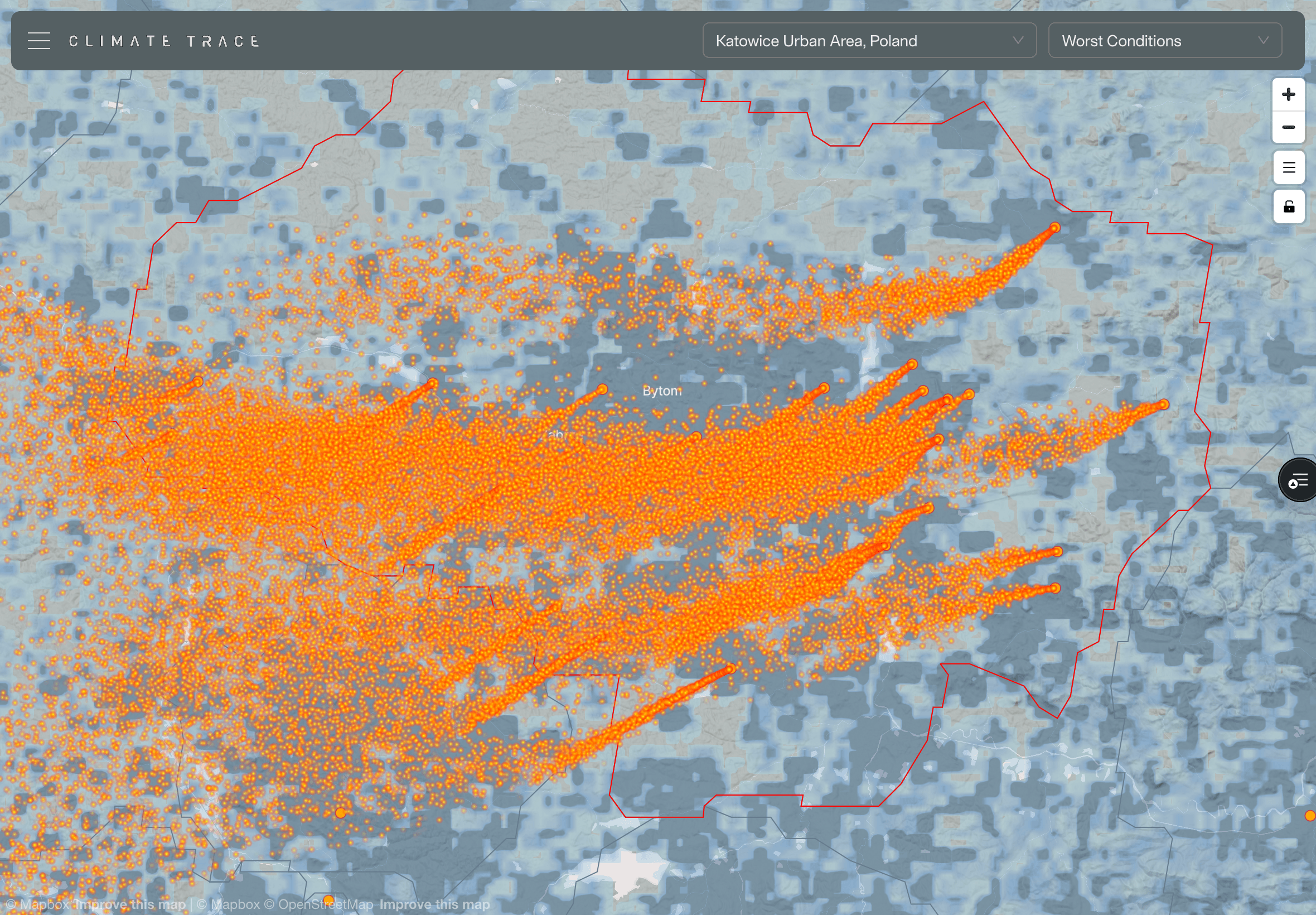

Finally, Climate TRACE has produce an open data platform for visualizing pollution plumes, based on data from satellites and other remote sensing technologies. A useful tool for seeing the unseen.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future content like this, as well as essays and transition-related briefings.