In this week's edition, the S-curve in climate policy, steps forward and backward in net-zero transitions, the politics of insurance, and the self-reinforcing feedbacks of economic inequality and climate change.

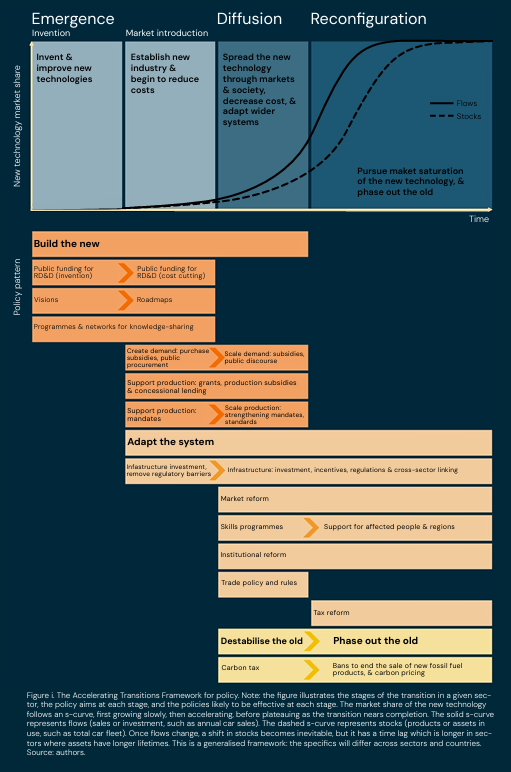

A new report on transitions policy design by Simon Sharpe's S-Curve Economics initiative (co-authored by Anna Murphy, Frank Geels, Johan Lilliestam and Anthony Patt).

In a nutshell, first build, then break.

Firstly, use policy to stimulate zero-emissions innovation, to build the technological alternatives that we need to grow over time. Secondly and subsequently, use policy to proactively squeeze old polluting technologies out of the system. See the summary slide below.

For New Zealand readers, note the difference with our current approach to climate mitigation policy. The New Zealand Government treats our Emissions Trading Scheme as the primary policy lever because it generates a price on emissions, with a default reluctance to adding other instruments to the policy mix. Meanwhile, public funding for R&D is in disarray; our innovation system has long lacked support for the 'demonstration' in RD&D; and there is no political will for subsidies or mandates. According to the S-Curve Economics view – which is informed by empirical evidence on how technological transitions actually happen in the real world – this is precisely the wrong way to think about the policy mix.

I agree – and I've written about an empirically informed approach in the New Zealand context for Policy Quarterly here and here.

Local transitions are possible! The chart below is from Jörn Scherzer (via LinkedIn), Head of Climate, Waste and Resource Recovery at Hutt City Council. As he says, ‘While others are still debating on whether to tackle emissions, or how best to save #OldManGas, we have been getting on with it.’

Jörn notes that Te Ngaengae Pool has just closed to swap out gas boilers for heat pumps, further reducing future emissions. These upgrades, worth $68 million, were co-funded by central government with $27 million from the Infrastructure Reference Group Fund, in partnership with Crown Infrastructure Partners.

But globally we are still off-track. Ahead of COP30, the Systems Change Lab has released its new State of Climate Action 2025 report.

There are plenty of positive trends, especially in electrotech deployment. Nevertheless, not one of the Lab's 45 indicators assessed is 'on track' to achieve its Paris-aligned 2030 target. Overall report card below.

An interesting essay by Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay on insurance as our climate-constrained world begins to squeeze… from one of my favourite newsletters, The Polycrisis, on Phenomenal World.

A dramatic climate-insurance breakdown that shocks the financial system of entire national economies will be preceded by something more banal, but perhaps equally sinister: years of more vulnerable communities getting more squeezed by a combination of ongoing extreme climate events, huge insurance premiums, and with it the quiet retreat of commercially-provided essential services like supermarkets, banking, and telecommunications. More affluent communities, on the other hand, may succeed, for a time, in obtaining public funding to protect themselves and their housing wealth.

... At stake is not the narrow insurers’ view of the “pooling of risks” or a dramatic wake-up moment of a doom loop prophesy, but rather a citizenry bound in “communities of fate” and the moral economy of the welfare state.

A new journal article by James Morrison, Jeroen van den Bergh & Giorgos Kallis on climate change and wealth inequality.

As shown in the figure below, wealth inequality and carbon emissions are in a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

We identify four potential mechanisms to explain why domestic wealth inequality is positively correlated with carbon emissions. First, wealthy elites can use their power to pursue their interests at the cost of environmental pressures through influencing the policymaking process. This is supported by evidence from the US which finds that policy tends to align with elite preferences, indicating limited influence from the median voter or organized groups of citizens. Second, wealth inequality is associated with higher emissions through carbon-intensive consumption by the rich. High wealth inequality provides greater means for the wealthiest to engage in forms of extremely carbon intensive consumption, such as owning yachts and private jets. Third, wealth inequality is likely to increase consumption by the whole population. Evidence from social psychology indicates that it is likely to induce increased status consumption across all of society as people feel a higher level of status anxiety in more unequal societies. Lastly, high levels of wealth inequality may lead to higher investment-related emissions. This is supported by research that finds investment-related emissions of the rich far exceed the consumption emissions of most people.

... We suggest that a more effective response to emissions associated with wealth inequality would be to target the ways that inequality leads to higher emissions. For example, a carbon tax would target the wealthy by increasing the cost of their luxury and status consumption, in turn reducing associated emissions and encouraging lower-carbon alternatives. Direct regulation of extremely carbon-intensive goods like yachts and private jets would further reduce emissions by the superrich. Additionally, the influence of elites on policymaking could be limited by strengthening democratic processes through greater regulation of lobbying and campaign finance, such as stricter limits on corporate and individual political donations or publicly funded election systems.

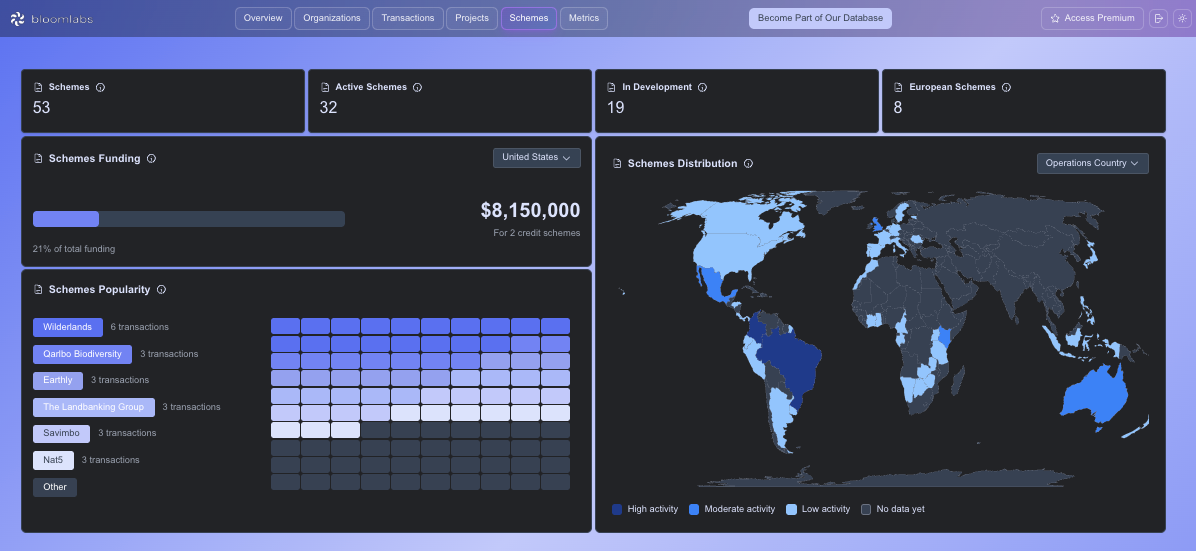

On nature finance, Bloom Labs has recently launched a new platform to analyse global transactions. Proud that Toha Network (my day job) is among the 50-odd schemes included for our MAHI pilot in Tairāwhiti.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future content like this, as well as essays and transition-related briefings.