Welcome to the first edition of The Brief, which summarizes the state of knowledge on various transition-related topics. Today's subject is the non-equivalence of biological removals and fossil emissions. This topic is inescapably technical, so some subscribers may prefer to read this lightly, or not at all. Please leave comments below if you want to dispute, correct, or extend on any aspect of this briefing. I will amend this to improve accuracy and keep track of versions. This is Version 1.2 (a few typos fixed).

Overview

1.1. A common presumption of carbon market design is the fungibility, or interchangeability, of emissions and removals of carbon dioxide. If emissions and removals are inversely equivalent – that is, if the climate heating impact of one tonne of carbon dioxide emitted (+1) is inversely equivalent to the climate cooling impact of one tonne of carbon dioxide removed (–1) – then the removal can be claimed to have perfectly negated (or ‘offset’) the impact of the emission (1 – 1 = 0).

1.2. This briefing examines the presumed fungibility between (i) carbon dioxide emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels and (ii) carbon dioxide removals by biological sinks such as forests, vegetation, soil, wetlands, sea grasses, kelp and so on. The problem of fungibility is broader than this (it includes, for instance, the treatment of short- and long-lived greenhouse gases, and non-biological removals such as carbon mineralization), but the scope of this briefing is narrowly focused on biological removals, primarily in forests.

1.3. A growing body of scientific evidence shows that the presumption of perfect fungibility between fossil emissions and biological removals is false. Biological removals do have a climate cooling effect, but it is not equivalent to fossil emissions on a like-for-like basis. If the signal of a carbon dioxide emission is +1 over (say) one-thousand years, then a biological removal is somewhere between –1 and 0. Effective ecosystem management can improve the durability of biological removals, thereby bringing the signal closer to –1, but the causes of non-equivalence cannot be managed away absolutely, especially as climate change multiplies the physical risks to terrestrial ecosystems (e.g. drought, fire, vector-borne pests and diseases).

1.4. At best, the presumption of perfect fungibility in carbon markets is a heuristic that reflects a genuinely compensatory relationship between biological removals and fossil emissions, but does so in a way that is systematically inaccurate. At worst, this inaccuracy introduces a degree of error that has non-trivial implications for mitigation pathways and climate change policy. Moreover, this error becomes amplified as reliance on carbon removals increases, as targets get nearer, and as Paris-aligned mitigation pathways steepen. Under these circumstances, a heuristic that might have been practically defensible in, say, the 1990s and 2000s is increasingly indefensible in the 2020s and beyond.

1.5. This briefing will, first, survey the science of non-equivalence; second, analyse the policy implications for New Zealand; and third, offer some recommendations to reduce the level of incongruity in New Zealand's climate change policy.

The science

2.1. Following Zickfield et al. (2023), there are four basic reasons why fossil emissions and biological removals are not inversely equivalent:

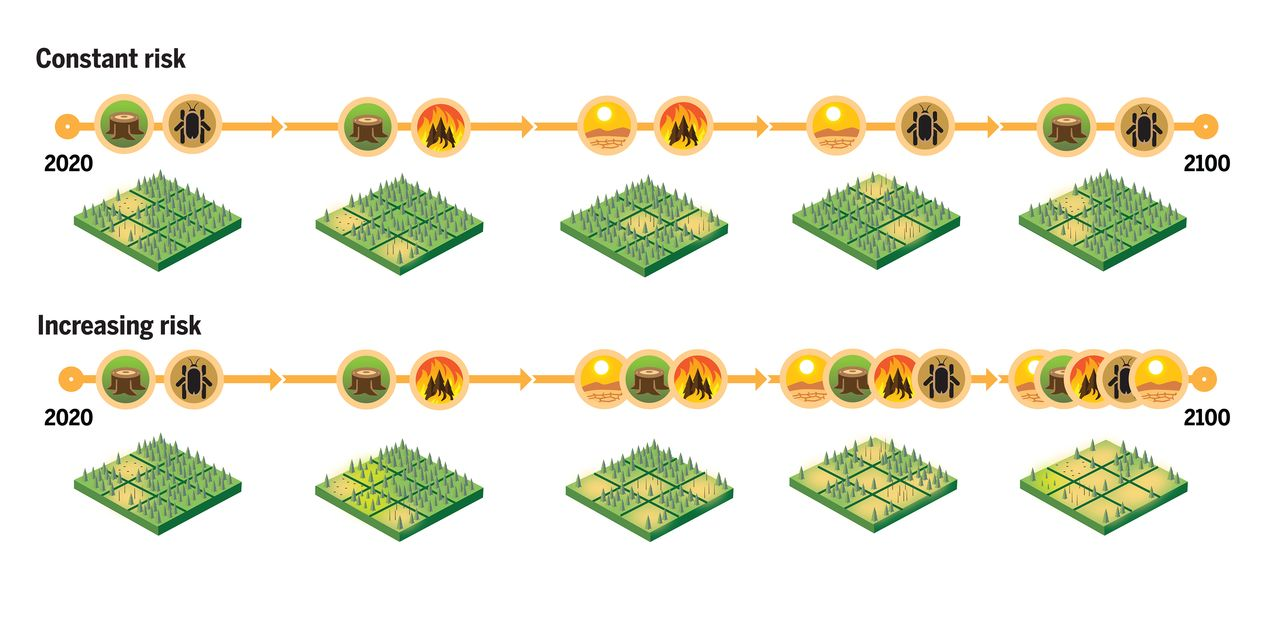

- 2.1.1. Lack of permanence: Carbon in the atmosphere is effectively permanent on timescales that are relevant for climate change (i.e. thousands or tens-of-thousands of years). Meanwhile, carbon in biological sinks, such as forests or wetlands, lacks durability over comparable timescales (Brunner et al. 2024). A forest might be harvested, burned, windthrown, or degraded by pests or diseases (Anderegg et al. 2020). A wetland might be drained for land use change, or evaporate in consecutive droughts. Even if such ecosystems reabsorb this carbon over time, the flux of carbon dioxide in and out of the atmosphere diminishes its overall signal. Consequently, offsetting a fossil emission with a biological removal is not a like-for-like exchange (Matthews et al. 2022). Rather, a permanent source of global heating is being compensated for by a more volatile, less durable sink.

- 2.1.2. Asymmetrical responses in Earth system: As the world heats, some of its effects are non-linear – that is, the change of the output is not proportional to the change of the input. If global heating is reversed, a lag is expected among variables in the Earth system, such as temperature, sea level, forest area, permafrost area, ocean heat content, and deep ocean acidity (Cao, Jin & Jiang, 2023). Furthermore, climate-induced changes to some variables may be irreversible. So, even if humanity succeeds in reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) from high to low levels, the Earth system will not return to its previous state. Taking this into consideration, Earth system modelling shows that ‘an emission of CO2 into the atmosphere is more effective at raising atmospheric CO2 than an equivalent CO2 removal is at lowering it’ (Canadell et al. 2021; see also Zickfield et al. 2021).

- 2.1.3. Altered earth surface: Biological removals can involve changes to land cover, such as afforestation, which has climate-relevant effects by altering the Earth’s surface. One example is albedo – that is, the reflecting power of different land cover types. For instance, the conversion of alpine grassland to dark pine forest will result in greater absorption of solar radiation and, hence, a warming effect that partially counteracts the cooling effect of carbon removals. There is still significant uncertainty over the strength of albedo effects, especially at mid-latitudes. However, the impact is not trivial: one global modelling exercise found that the reduced albedo from expanded forest cover reduced the climate response of reforestation by about 45% (Matthews et al. 2022).

- 2.1.4. Other associated emissions: The production and consumption of fossil fuels not only produces emissions of CO2, but also methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), water vapour (H2O) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), a precursor of sulfate aerosols. The heating effects of CH4 and N2O (and the cooling effect of sulfate aerosols) are additional to the effect of CO2, so cannot be perfectly neutralized by a CO2 removal. In aviation, the production of water vapour by jet engines results in contrails, which under certain conditions can develop into artificial cirrus clouds that trap outgoing heat. These effects complicate the oversimplifying assumption that a CO2 removal will negate the climate warming impact of a CO2 emission, because the latter is associated with non-CO2 effects as well. Conversely, biological removals are a product of ecosystems that also generate non-CO2 emissions. For instance, forests act as both sources and sinks of CH4 and N2O, with the net effect depending on a range of variables including the previous land use, selected tree species, soil type, climatic factors and management systems (Zickfield et al. 2023). Also, forests produce biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs), such as terpenes. These function as an indirect greenhouse gas by oxidizing rapidly into organic aerosols and ozone (O3) which, in turn, prolongs the atmospheric lifetime of methane and therefore its heating effect. The overall impact of non-CO2 effects are highly complex and subject to significant uncertainty, highly dependent on the specifics of each ecosystem.

2.2. As a consequence of these four factors, ‘it is expected that balancing a fossil fuel CO2 emission with a removal of equal magnitude will result in a different climate outcome than would occur in the case of avoiding the fossil fuel emission’ (Zickfield et al. 2023).

The policy implications

3.1. The main takeaway for policy makers is that, insofar as net-zero pathways assume perfect fungibility between fossil emissions and biological removals, they are propagating an error, or rather a heuristic that is systematically inaccurate. The greater the overreliance on biological removals to achieve net-zero, the more that inaccuracy will be amplified, especially by the reversal risks that such an approach entails.

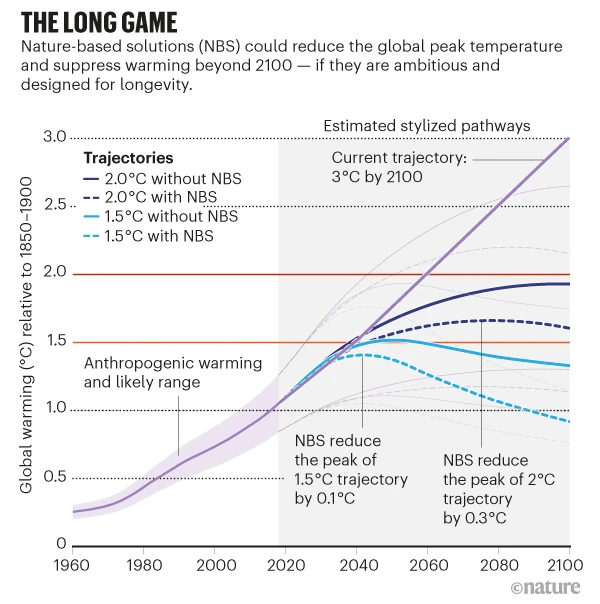

3.2. It does not follow from this that biological removals do not have an important role in credible mitigation pathways. On the contrary, the carbon that biological sinks remove is genuine, so biological removals can and should play well-defined roles in future mitigation pathways (e.g. Girardin et al. 2021; see the figure below). The argument is rather that biological removals are not a ‘mirror image’ of fossil emissions and, therefore, cannot be expected to perfectly neutralize the latter’s climate heating effect. Climate mitigation efforts, both voluntary and regulatory, need to reflect this fact; otherwise they will lack credibility and integrity.

3.3. One of the challenges in addressing this topic is that, historically, the presumption of perfect fungibility between biological emissions and fossil emissions was widely embedded in prevailing accounting standards, including the methodologies that underpin New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS). Thus, in spite of early warnings about non-equivalence (e.g. Steffen, Fenwick & Rice, 2016), countries and companies were able to use the heuristic of equivalence without a breach of existing accounting standards. However, the growing divergence between new science and old climate accounting is a source of future risk and uncertainty in carbon markets, because these anomalies cannot be ignored forever.

3.4. On the issue of carbon dioxide removal (CDR), Stuart-Smith et al. (2023) argue that the Paris Agreement and associated COP decisions ‘create a normative pull (a legal direction travel) toward aligning short-term NDCs with long-term strategies and encouraging states to lay out pathways to the global temperature goal that are rooted in scientific evidence. Emission-reduction pathways that depend heavily on CDR, given their corresponding risks and uncertainties, go against the grain of these provisions… CDR-dependent pathways that involve substantial risks are not in keeping with norms and principles of international law’ [emphasis added]. Thus, in the spirit of ‘ambition raising’ under the Paris Agreement, accounting practices and policy norms are likely to evolve over time to incorporate new science and policy knowledge. Indeed, the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) and the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body are already debating how to incorporate this science into accounting standards, to the extent that some scientists are concerned about an overcorrection (Evans, 2025). For countries and companies that are highly reliant on biological removals, this poses the foreseeable risk that their net-zero strategies will be increasingly misaligned with global norms and market expectations.

3.5. Regulation is one domain where this correction is likely to manifest, both in consumer protections for corporate claims of sustainability and also the accounting assumptions that underpin environmental regulations:

- 3.5.1. The EU’s Green Claims Directive (to be enforced by September 2026) intends to prohibit the making of claims, such as ‘carbon-neutral’ or ‘carbon positive’, based on the offsetting of greenhouse gas emissions. Rather, claims will only be allowed when they are based on the actual lifecycle impact of the product within its own value chain (i.e. decarbonization rather than offsetting).

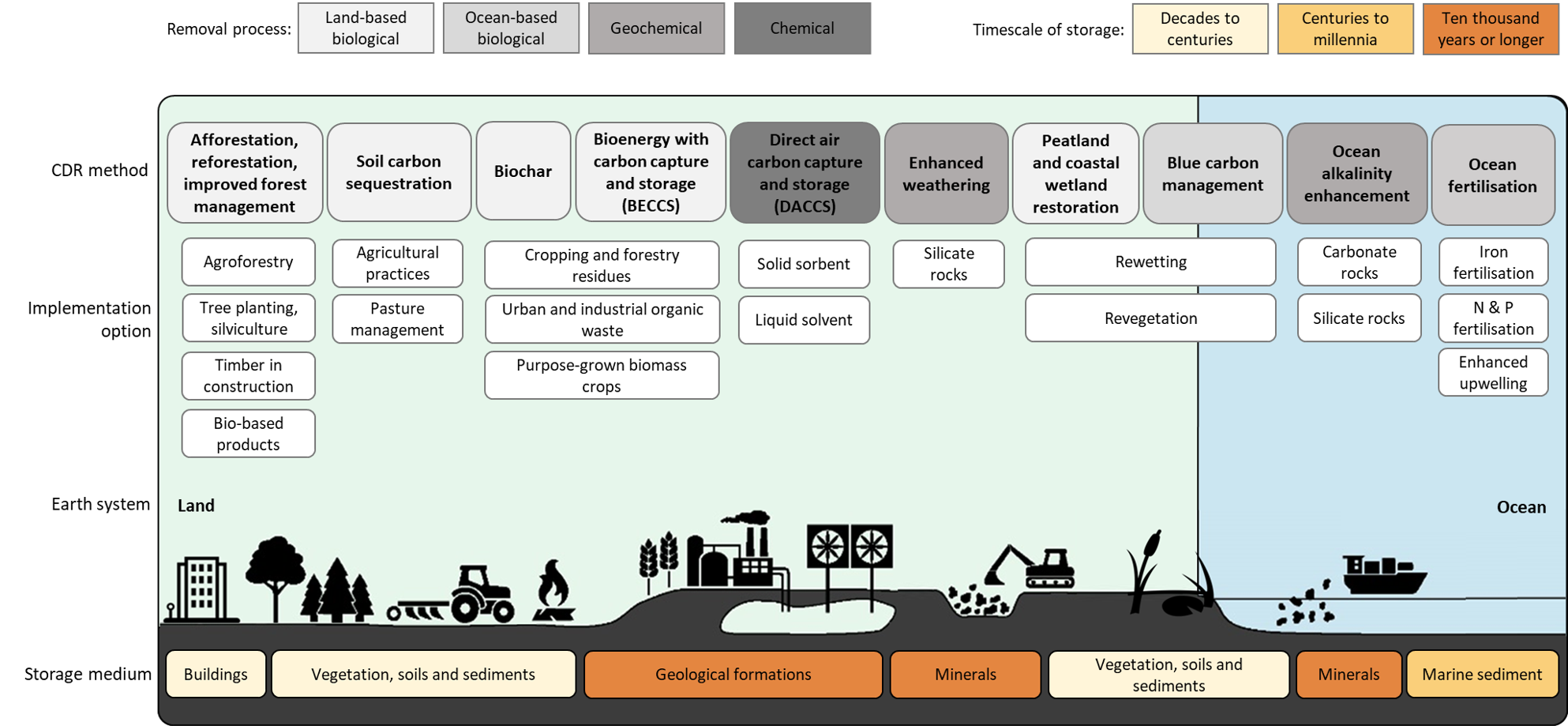

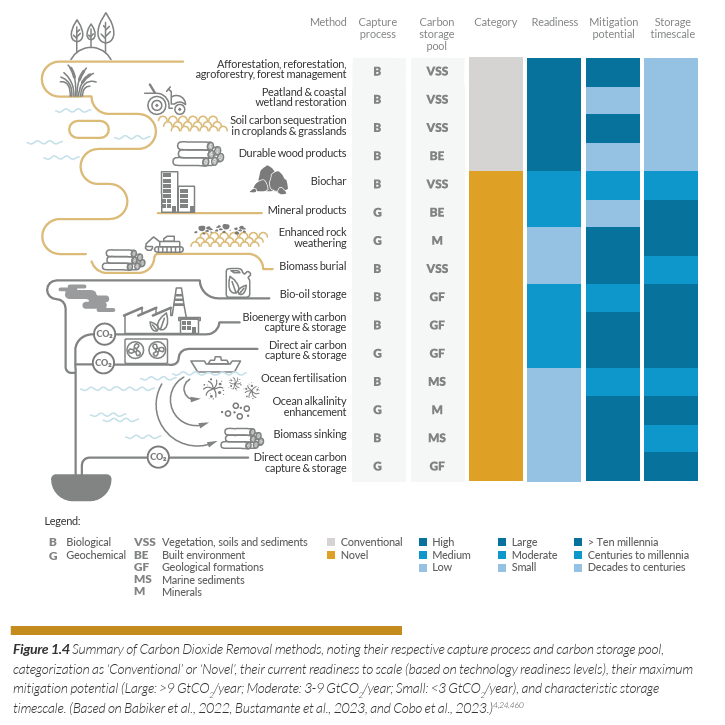

- 3.5.2. The European Parliament also recently extensively debated the role of carbon dioxide removals for offsetting residual, or hard-to-abate, emissions within the EU ETS. The ‘like-for-like’ approach was highly contested, with the EU ultimately deciding that fossil emissions can only be compensated with permanent removals that store carbon securely and durably for several centuries, such as direct air carbon capture (DACC), biochar with carbon removal, and enhanced rock weathering. (For a summary of removals types, see the figure below.)

3.6. Climate litigation is another mechanism by which this correction might be compelled. Stuart-Smith et al. (2023) warn that litigation might be used to challenge the treatment of removals in country-level mitigation pathways and/or corporate net-zero strategies. Indeed there are already local examples of this occurring:

- 3.6.1. The Federal Court of Australia dismissed the principle of perfect fungibility in its final decision on Parents for Climate vs. EnergyAustralia, which related to the latter’s Go Neutral carbon offsetting scheme. In May 2025, the Federal Court found in favour of the statement of claim which argued that ‘short-lived storage’ of carbon in ‘biotic sinks’ increases the quantity of carbon at risk of reversal from natural or human processes, thus contributes to ‘an increase in the atmospheric concentration of GHGs contributing to further climate change and global warming’. Subsequently, EnergyAustralia retracted the scheme and publicly acknowledged that: ‘offsets do not prevent or undo the harms caused by burning fossil fuels… EnergyAustralia today accepts the scientific consensus that these “offsets” do not indefinitely remove greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels, because carbon is stored in plants for a substantially shorter time than those emissions remain in the atmosphere. Storing carbon in plants is not equivalent to keeping it stored in fossil fuels (by not burning those fossil fuels in the first place).’

- 3.6.2. Lawyers for Climate Action NZ (LCANZ) and Environmental Law Initiative (ELI) launched legal proceedings against the Minister of Climate Change in June 2025 to allege that the New Zealand Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) fails to fulfil basic requirements of the law. LCANZ and ELI intend to argue that the ERP’s presumption that forestry offsets and reductions are fungible rests on a fundamental error of fact. This will be one of the first legal cases in the world to challenge a government’s overreliance on carbon offsetting.

3.7. The relationship between policy and science is complex. Science does not wholly determine policy; rather, it is one of many contributing factors to policy processes that also involve legal consistency, economic constraints, political factors (e.g. electoral strategy), geopolitics, and so on. Nevertheless, science does have an influence on what policy can be treated as rational or ‘evidence-based’. Furthermore, good science underpins good policy by accurately describing the physical aspects of policy problems, and the causal processes that link a policy instrument to its desired outcome. Consequently, we should expect to see ongoing pressure – from inside and outside the policy system – to reduce the anomalies between the science of non-equivalence and the current policy approach.

Managing policy risks

4.1. To reduce the risk of science-policy misalignment and the negative impacts of future corrections to climate accounting, it is prudent for New Zealand policy makers to be responsive to the emerging science on non-equivalence (e.g. Cullenward 2023).

4.2. The risks to New Zealand are amplified by its relatively heavy reliance on forestry removals for meeting its international and domestic targets, because this disproportionately exposes New Zealand to transition risk if and when the norms and standards of climate accounting change. The proposed inclusion of other types of biological removals under the New Zealand Government’s new Assessment Framework for Carbon Removals (Ministry for Environment, 2025) would further increase the risks of misalignment. Therefore the need for a prudent approach.

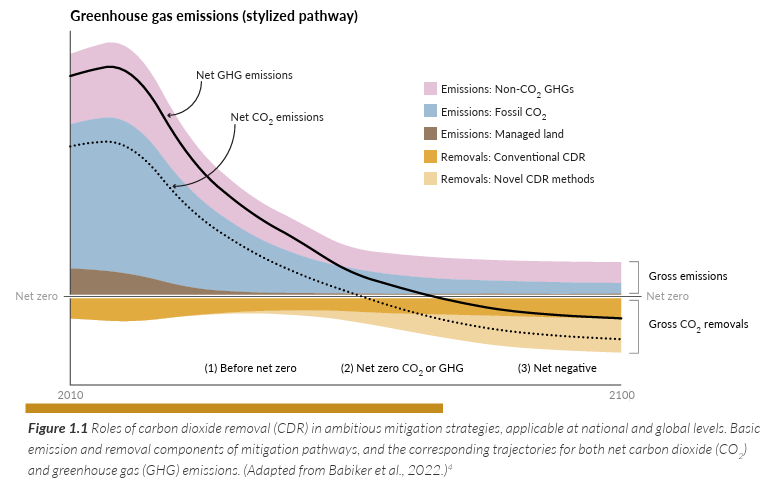

4.3. The fundamental step to addressing the issue of non-equivalence is to develop a coherent, comprehensive and credible removals strategy to 2050 and beyond. In its Sixth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified three roles for carbon dioxide removal (CDR): ‘(i) further reduce net CO2 or GHG emission levels in the near-term; (ii) counterbalance residual emissions from hard-to-transition sectors, such as CO2 from industrial activities and long-distance transport (e.g., aviation, shipping), or methane and nitrous oxide from agriculture, in order to help reach net zero CO2 or GHG emissions in the mid-term; (iii) achieve and sustain net-negative CO2 or GHG emissions in the long-term, by deploying CDR at levels exceeding annual residual gross CO2 or GHG emissions’ (Babiker et al. 2022; see also Smith et al. 2024). This is visualized in the chart below.

4.4. In 2023, the New Zealand Government endorsed the IPCC’s removals strategy in its submission to the Supervisory Body of the Article 6.4 Mechanism. Currently, however, New Zealand only uses eligible forestry removals in a net-based approach for achieving international and domestic targets. Recently, the New Zealand Government has also rejected the Climate Change Commission’s advice to incorporate a net-negative long-term target for long-lived emissions, including CO2. This poses the question of how New Zealand will transition toward the mid- and long-term uses of removals – i.e. offsetting hard-to-abate emissions and achieving net-negative emissions.

4.5. Internationally, there are signs that the transition toward the IPCC’s recommended strategy is already underway, with voluntary and compliance carbon markets bending toward a more discerning use of carbon removals for offsetting hard-to-abate sectors.

- 4.5.1. In voluntary markets, the Draft Corporate Net-Zero Standards (V2) by Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is proposing that companies ‘phase out the use and support of unabated fossil fuels, allowing only limited residual uses that will be neutralized to achieve net-zero.’

- 4.5.2. In compliance markets, the minority of countries that include forestry removals in their ETSs have quantitative (as well as qualitative) limits on their use. For example, the California ETS has a 6% limit on forestry removals for surrender obligations. Similarly, the EU Parliament, after extensively debating the appropriate use of carbon removals in the EU ETS, decided to include international units at a limit of 5% of total emissions and, as noted earlier, only allows permanent domestic carbon removals to compensate for hard-to-abate emissions. Improving the management and resilience of biogenic sinks, such as forests or wetlands, can prolong the storage of carbon and reduce the risk of reversal. This can reduce, but not eliminate, one of the factors of non-equivalence.

4.6. If global markets continue to evolve in this direction, New Zealand’s exporting companies will have incentives to limit the use of biological removals in their net-zero strategies, and instead to exploit New Zealand’s potential for low-emissions economic production, particularly by leveraging New Zealand’s relatively high share of renewables (≈85%) in its electricity supply. In this context, a national policy framework that relies too much on biological removals to reduce net-emissions, and not enough on reducing gross emissions, might disadvantage exporters who pursue a competitive advantage by lowering the emissions intensity of goods and services.

4.7. Mitigation pathways to net-zero and beyond are an intergenerational endeavour. Decisions made, or not made, today have a significant bearing on the viability of long-term objectives. For example, if carbon offsetting markets exhaust the land available for afforestation in the near- to mid-term, then the future contribution of forestry to net-negative emissions will be foreclosed. Therefore, a long-term strategy is critical to a no-regrets approach that spreads costs over time, does not overlook near-term risks or opportunities, and avoids shifting unreasonable burdens onto future generations. The potential elements of such a strategy for New Zealand might include the following:

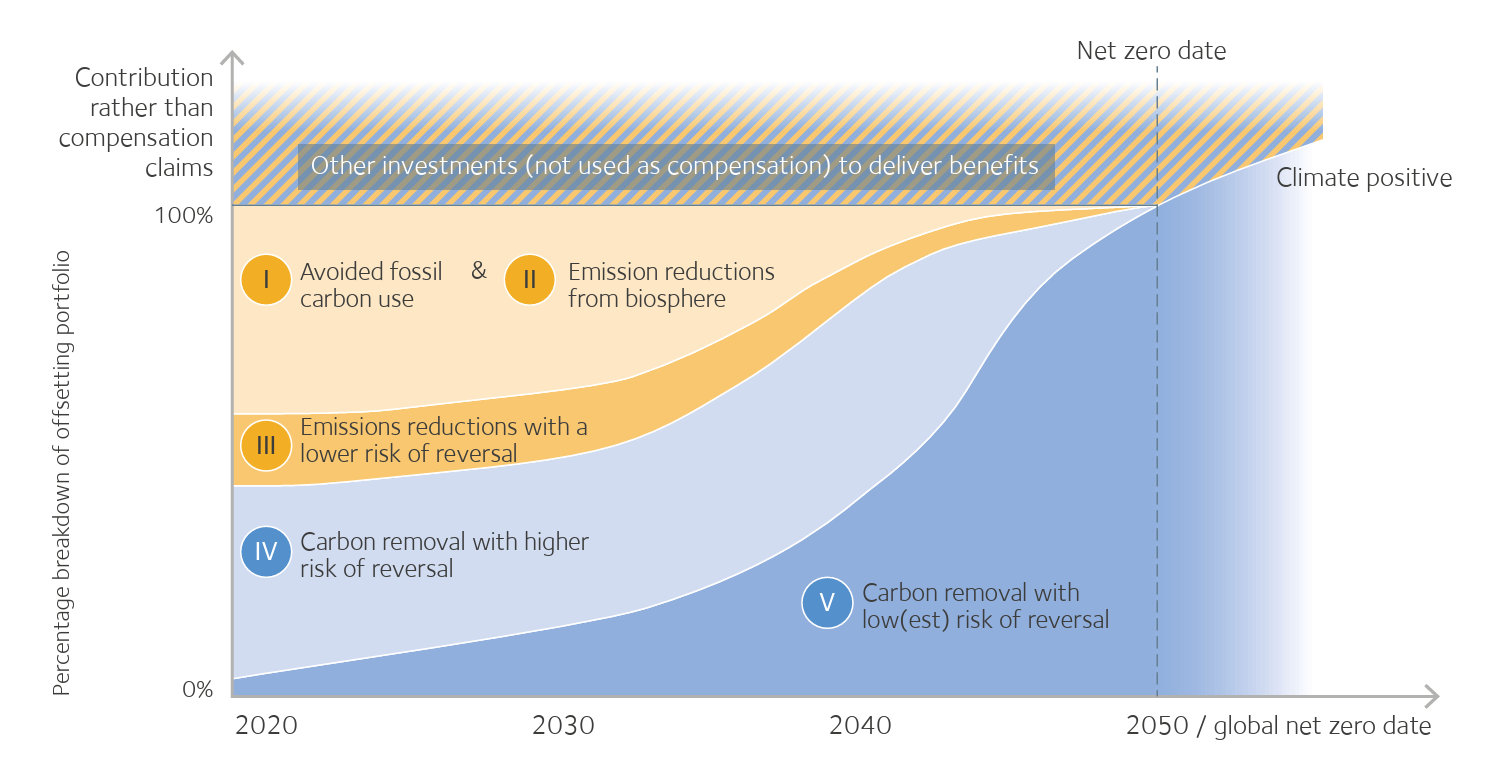

- 4.7.1. Implement a shift from (i) the use of biological removals for offsetting fossil emissions indiscriminately to (ii) the use of permanent removals with durable storage to compensate for residual emissions by the net zero target date. This like-for-like approach is consistent with the Oxford Offsetting Principles (Axelsson et al. 2024) and the concept of ‘geological net zero’ (Allen et al. 2025; Frame & Macey, 2025). This transition need not occur instantly, but should be complete once global net-zero is achieved (as shown by the figure below).

- 4.7.2. Meet the implied future demand for durable storage by scaling up permanent removals technologies, such as direct air carbon capture (DACC), biochar with carbon removal, and enhanced rock weathering (see figure below). This will require importing technologies and practices from overseas, but also supporting domestic research, development and deployment (RD&D) to stimulate innovation and overcome market barriers for permanent removals (Smith et al. 2024, chs. 2 & 3).

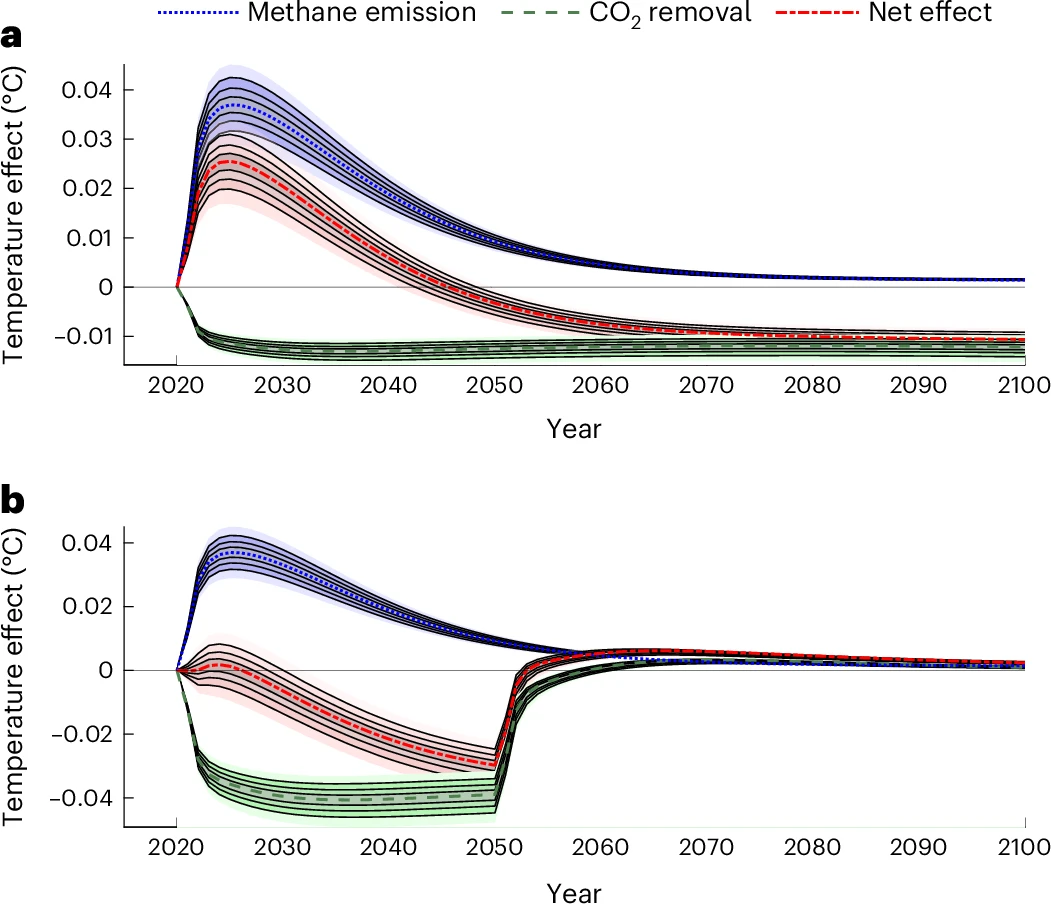

- 4.7.3. Implement a complementary shift toward matching short-lived storage (e.g. biological removals) with short-lived emissions (e.g. biogenic methane) for offsetting. There is a growing body of research which shows that improved equivalence is possible through better temporal matching of removals and emissions (e.g. Frame & Melia, 2022; Matthews et al. 2023; Venmans, Rickels & Groom, 2025). This would address doubts about the integrity of existing carbon markets by repurposing biological removals for a more suitable purpose.

- 4.7.4. Improve the management and resilience of biogenic sinks, such as forests or wetlands, to prolong the storage of carbon and reduce the risk of reversal (e.g. Keenan 2015). This can reduce, but not eliminate, one of the factors of non-equivalence, and thereby improve the integrity of historical approaches to carbon offsetting.

- 4.7.5. Improve risk management of carbon reversals by shifting to the use of permanent removals to compensate for any loss of biological carbon. Therefore, biological removals can serve as a bridging technology for permanent removals (Streck et al. 2025), where the latter effectively locks in the transitional impact of the former. The objective is to develop a mutually reinforcing portfolio of more and less durable removals that mitigates future climate-related risks.

- 4.7.6. Avoid an overreliance on biological removals by prioritizing drastic reductions to gross emissions. This is for four reasons:

- Firstly, by reducing its exposure to biological emissions, New Zealand reduces the transition risks from a correction to climate accounting.

- Secondly, if global gross emissions are not reduced, the mitigation benefits of biological removals cannot be realized, because the climate-related risks of carbon reversal will increase. A recent modelling exercise of net-zero mitigation pathways showed that biogenic sinks like forests can reduce the magnitude and duration of the temperature peak, but only if global gross emissions are also simultaneously reducing (Matthews et al. 2022).

- Thirdly, by reducing gross emissions, New Zealand increases its exposure to the spillover benefits of decarbonization, which include the competitive advantage for low-emissions exports; the commercial value of homegrown technologies that reduce emissions and climate impacts; the improved trade balance from reducing offshore fossil fuel imports; and the energy independence of renewable energy systems that rely on water, wind and solar.

- Fourthly, a commitment to reducing gross emissions reduces the moral hazard of permanent removals – that is, the temptation to reduce ambition for decarbonization on the presumption that future technologies will permanently remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

- 4.7.7. Execute the above by phasing out the use of forestry removals to meet surrender obligations in the New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS), either by capping the overall volume of forestry removals, or restricting the use of forestry removals to hard-to-abate sectors and/or short-lived emissions. The idea of a phase-out has circulated informally for years, articulated recently by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE, 2025); however, his proposal lacks an analysis of the distributional impacts and therefore the political economy barriers to change. Consequently, this phase-out needs to be part of a just transition plan that addresses the associated economic losses to forest owners, especially Māori forest owners who reached settlements with the Crown on the expected value of future carbon revenue. A vital opportunity is the creation of markets for contribution claims (see below), rather than the compensation approach of the NZ ETS.

- 4.7.8. Implement markets for climate contributions that operate alongside carbon offsetting markets, with the intent of shifting market participants from the latter to the former. Essentially, this involves shifting the market from compensation claims (i.e. offsetting) to contribution claims – that is, claims that a company has contributed to a local or global target by investing in impact beyond its own value chain (e.g. Fearnehough et al. 2023; Chagas, Streck & Trouwloon, 2025). For example, instead of a company purchasing a biological removal to claim carbon-neutrality, the company would claim to have contributed toward New Zealand’s climate commitments (e.g. a contribution to the Nationally Determined Contribution). Climate contribution markets are advantageous for the following reasons:

- A contribution approach is ‘more scientifically accurate, straightforward and legally defensible, reducing legal and reputational risks… because it does not presume equivalence between the climate mitigation benefits of [biological removals] with the harms of greenhouse gas emissions’ (Anderegg et al. 2025).

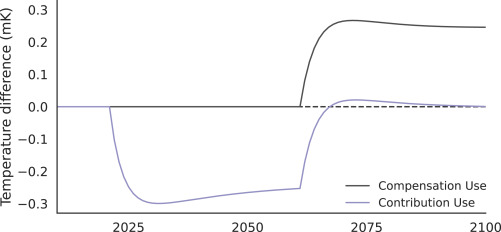

- Contributions lower the stakes of carbon reversals. Consider a forest lost to wildfire. If the forest was financed through the sale of carbon credits for compensation claims (i.e. offsetting), then the outcome is a net-gain in atmospheric carbon, because the stored carbon is no longer offsetting those emissions (see the chart below). However, if the forest was funded through the sale of carbon credits for contribution claims, then the outcome is a return to the baseline, as if the action had not occurred (Cullenward, Badgley & Chay, 2023).

- The global community needs climate contributions to succeed if it is to achieve the third phase of the IPCC’s removals strategy – that is, the transition to net-negative emissions. By definition, this can only be achieved if, in addition to the offsetting of residual emissions by an equivalent volume of permanent removals, there is a flow of carbon removals occurring (i.e. negative emissions) that are not linked to offsetting (see the top-right corner of the figure in §4.7.1).

- A viable market for contribution claims can serve as a transitional enabler for the phase-out of forestry removals from the NZ ETS, because it would provide an alternative revenue stream to carbon offsetting. The loss of NZ ETS revenue would therefore be compensated (in part or in whole, depending on the mechanism), enabling a just transition. Moreover, forest owners would transition to a more credible market for biological removals, which is consistent with the IPCC’s long-term strategy for carbon removals.

- Contributions enable recognition of the carbon co-benefit that eventuate from investments into nature for biodiversity or adaptation benefits (e.g. biodiversity credits, ecosystem-based adaptation).

Conclusion

5.1. The science of non-equivalence is sometimes seen as a threat by the advocates of nature-based solutions. The fear is that, by recognizing the risks of biological removals, their importance is being dismissed or downplayed. However, the problems associated with non-equivalence do not lie with any shortcomings of biological removals. Rather, the problems lie with the inappropriate purposes that they have been recruited for. It is the specific purpose of offsetting fossil emissions for which biological removals are naturally unsuited.

5.2. However, biological removals can be enlisted for alternative purposes for which they are eminently suitable. One purpose is the offsetting of short-lived emissions. Another purpose is contribution claims, which is distinct from the compensatory logic of offsetting. These purposes treat biological removals as they actually are, directing their benefits to purposes for which they are suited. This is the pathway to a coherent, credible system for biological removals, which ultimately will also benefit the stewards and managers of nature-based solutions.

Thanks for reading this far! If you haven't already, please subscribe to receive future content like this, as well as essays and transition-related briefings.